More pregnant women and new mothers are dying from pregnancy- and childbirth-related causes in Georgia than nearly anywhere else in the nation. And Black women in the state are over two times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than their white counterparts.

“This is a crisis in Georgia,” said Wanda Thomas, senior director of underrepresented in medicine and chief diversity officer for Mercer University’s School of Medicine. “We want to bring awareness to that and mitigate some of those health disparities that may cause this.”

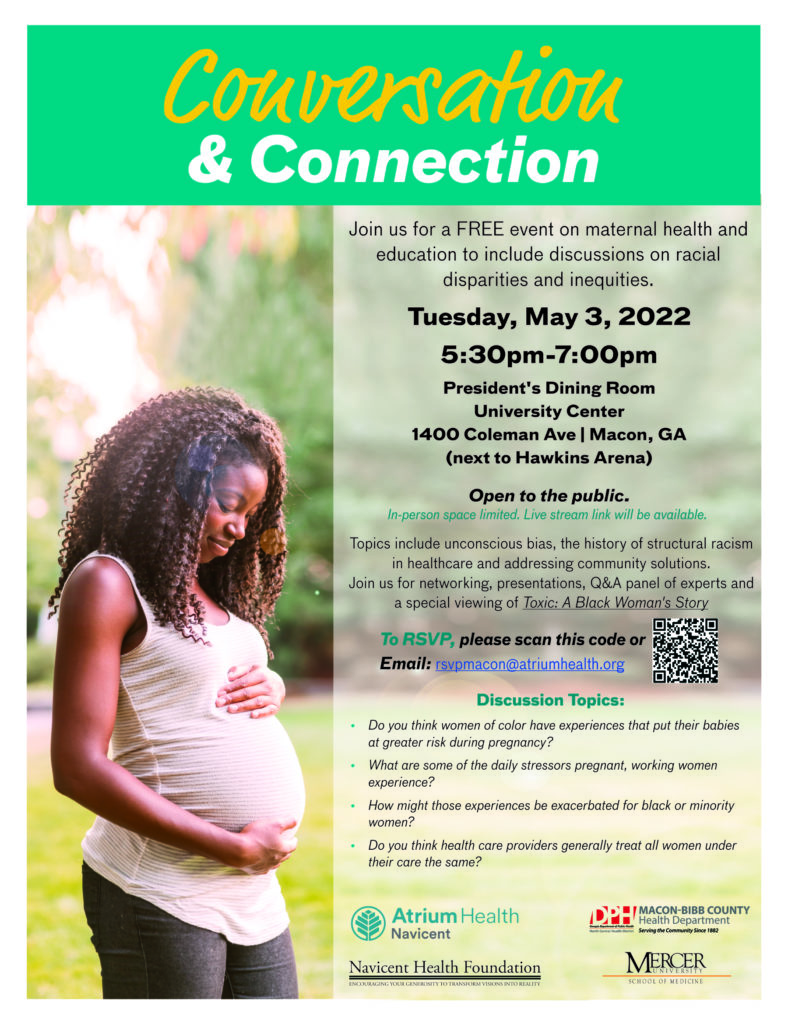

To that end, the School of Medicine and Office of Diversity and Inclusion, along with Atrium Health Navicent and other partners, are holding a free event on May 3 to educate the community and health care providers about racial disparities and inequities in maternal health care, as well as discuss solutions.

Dr. Patrice Walker, chief medical officer at Atrium Health Navicent, will kick off the event with a presentation about unconscious bias. That will be followed by a screening of the short film, “Toxic: A Black Woman’s Story,” and a question-and-answer session with a panel of experts.

The panel will include Dr. Walker; Dr. Jacob Warren, director of the Center for Rural Health and Health Disparities at Mercer; Dr. Jimmie Smith, administrator of the Macon-Bibb County Health Department; Dr. Felisha Kitchen, an OB-GYN specialist; and Patricia Prime, a registered nurse and certified postpartum doula.

“Now that we know it’s a problem, we can’t ignore it,” Dr. Walker said. “We really have to try to find solutions because it’s our moms, our society that’s really hurt by that.”

Among the factors that contribute to health disparities among Black women is unconscious bias.

Unconscious bias, which is also known as implicit bias, is the brain’s way of categorizing and making sense of the world. It’s why our brain categorizes lions, for example, as a dangerous animal and signals our bodies to run, Dr. Walker said.

“But when you get into higher order situations that are not like an animal out in the forest, sometimes those categories are not black and white, and I think that’s really where we can run into problems with unconscious bias, when we try to lump people into categories,” she said.

“As human beings, we don’t always fit nicely into a box, and so we have to attempt to not allow the box that our brain wants us to put people in and really understand specific details about people to make sure we are not limiting ourselves in our interactions with them based off of what we think we know.”

In a health care setting, that may look like physicians making assumptions about patients labeled “noncompliant” when they don’t follow doctor’s orders. Patients may want to be compliant but face other barriers, such as a lack of transportation, that prevents them from following orders, Dr. Walker said.

Once patients are labeled noncompliant, unconscious bias may cause doctors to assume they won’t listen and limit their guidance, she said.

“We see that in health care many times, that a provider will make a determination about what they think a patient will or will not do, and then that affects the counseling or that affects the interaction that they have with that patient,” she said.

Racism also plays a role in maternal health disparities. Research shows that regardless of socioeconomic status or education, Black women still face a higher risk of negative outcomes than white women, Dr. Walker said.

“If there’s not a racism aspect to it and if it’s more about social determinants, then those Black women who make more money, that have access to the best health care and insurance, you would think that those women would be at a decreased risk, but studies show that they’re not,” she said. “So, that component of racism really can’t be ignored.”

In addition, the country’s history of structural racism in health care contributes to disparities by causing many Black people to distrust the health care system, Dr. Walker said.

“That may delay (them from) getting maintenance care, such that when they do present, they are that much sicker,” she said. “And if there are social barriers on top of that, like insurance or transportation, then that just compounds the problem even more.”

The maternal health event will take place 5:30-7 p.m. May 3 in the Presidents Dining Room in the University Center on Mercer’s Macon campus.

The event is open to the public, but in-person space is limited, so attendees are asked to reserve a spot by emailing rsvpmacon@atriumhealth.org. For those who cannot attend in person, the event will be live streamed on the Atrium Health Navicent Facebook page.

Additional event sponsors include the Navicent Health Foundation and Macon-Bibb County Health Department.

“I hope that people will take away from this event the seriousness of maternal mortality because families need their mothers, and hopefully we can bring awareness to some of the factors that bring on women’s mortality after childbirth,” Thomas said.