Editor’s note: This story originally appeared in the Spring 2023 edition of the Global Health in Action Newsletter, which was focused on stories of resilience. Click here to read more.

As an elementary schooler, Mercer University alumnus Raymond Partolan loved playing in the woods behind his family’s apartment building in Macon. He loved how cold the creek felt on his feet and ankles as he waded through the water. He enjoyed catching frogs, gathering stray sticks and branches, and hearing the rustle of the brush and leaves as his best friend and next-door neighbor played nearby under the trees.

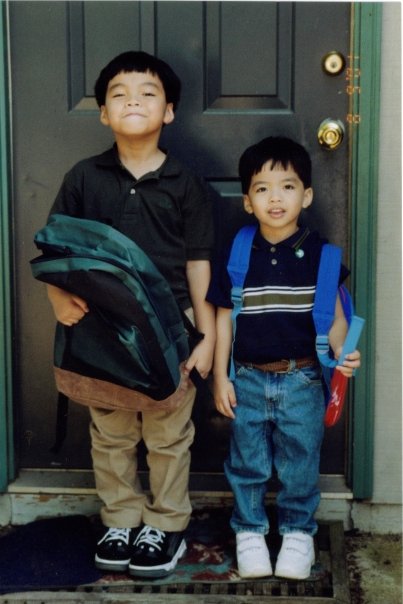

He loved being a kid and a self-proclaimed “Georgia boy.” His afternoons were spent playing with his PlayStation video game console, reading books, watching movies, and spending time with his younger brother and parents.

Despite his vibrant and comfortable home life, school was not always a safe place for Partolan, an Asian American child growing up in the Deep South. He still recalls some of his earliest memories of having racist language hurled at him while classmates told him to “go back to China,” a country nearly 2,000 miles away from the Partolan family’s country of origin — the Philippines.

While much of Partolan’s extended family calls the southeast Asian country home, he only spent one year of his life living in the Philippines, a country he said he has “zero recollection” of. His father, a physical therapist, and his mother, a paralegal, moved with Partolan to the United States in 1994, hoping to find new opportunities and a place to raise their young family.

In 2003, it came time for Partolan’s father to replace his work visa — and the rest of the family’s dependent status — with green cards, which would guarantee their permanent residency and permission to live in the United States long term.

“In order for us to obtain our green cards, my dad had to pass this English competency exam called the TOEFL, the Test of English as a Foreign Language,” Partolan said. “He was able to pass every section of that test, except for the speaking section. He retook the test over and over and over again, and unfortunately, he just never could get a passing score.”

The family’s green card applications were denied, and the Partolans “started living in fear every single day of being arrested and deported” back to the Philippines, Partolan said. He was only 10 years old.

“We as a society don’t really talk a whole lot about undocumented Asian Americans because people see this issue of immigration mainly as a Hispanic or Latino issue. Growing up, after becoming undocumented, I just felt very isolated. I felt very alone,” Partolan said. “It was compounded by the fact that my parents basically instilled in me this notion of not sharing my immigration story with anyone because telling the wrong person could endanger us and put us at risk for deportation.”

This fear followed Partolan through high school as he competed with his school’s academic team, played in the orchestra, and founded the Rubik’s Cube club on campus. He watched his classmates get driver’s licenses, their first jobs and plan for college — things he was unsure he would ever be able to do because of his immigration status.

“This all really boiled over to a point when the fall of my junior year of high school, I actually tried to take my own life because I had just lost my will to live. I lost my drive, my motivation to continue being on this planet,” Partolan said. “I felt like this country didn’t want me here, and there was absolutely nothing that I could do about it.”

He described his close encounter with death and his struggle planning for college as a “period of awakening” in his life, igniting his passion for advocacy and for inspiring change in the United States’ “broken immigration system.” He began sharing his story and struggles with his immigration status with friends and teachers, even speaking to crowds of students and community members at larger events.

In the months following his suicide attempt, the University System of Georgia’s Board of Regents introduced two new policies: one barring undocumented students from attending the five most selective colleges in the state and a second requiring undocumented students living in Georgia to pay out-of-state tuition at in-state schools. The barriers to receiving a college degree seemed even more insurmountable to Partolan, who now felt confined to only applying to private institutions where the tuition was equal for all students regardless of immigration status.

He applied to 14 private colleges and universities during his senior year of high school before deciding to attend Mercer to study political science and Spanish as a Presidential Scholar with plans of attending law school. Partolan graduated high school as the class salutatorian and prepared to start college classes in his hometown of Macon.

Then, when he was 19 years old, the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program was implemented by then-President Barack Obama, making Partolan eligible for work authorization and a driver’s license and protecting him from deportation for two years. He got a job and moved into a house down the street from Mercer’s campus, eager to start “building a life for himself,” he said.

“At the time, I was feeling such a huge deal of resentment towards my family. Specifically, my mom and dad. I kept asking myself, how could my parents put me in this impossible situation? How could my dad fail to pass this English test, resulting in us losing our status and becoming undocumented?” he said said. “So at the time, I just wanted to get as far away as I could from my family.”

Partolan remembers his years as an undergraduate student as a “magical experience.” His community involvement continued and grew as a college student, as he engaged with his classmates at Mercer by being a peer adviser and competing on the mock trial team. He was elected president of the Student Government Association (SGA) as a junior, making him the first Asian American and undocumented student to serve in the role.

“When I was on Mercer’s SGA, I used the opportunity to work with Mercer’s administration to try and develop impactful and innovative programs to support undocumented students at Mercer,” he said. “After I started publicly sharing my story and talking to people about my lack of immigration status, more and more people started coming out and telling me that they, too, were undocumented.”

His advocacy efforts as a young person expanded outside the college campus to include engaging in community organizing projects with other undocumented people in the Atlanta area. In 2013, when Partolan was a sophomore in college, he was involved in a lawsuit against the state of Georgia urging it to reverse its policy prohibiting in-state tuition for undocumented students. While the lawsuit was unsuccessful, Partolan said it thrust him into the advocacy space and established his desire to pursue a career in community organizing.

“For the first time in my life, I felt like I had agency. I felt like I had initiative, and I felt like I had some kind of control over the way things went down in my life,” he said. “I had control over whether I was going to stand up and fight for myself and for my family and for our community, or if I was just going to sit back and watch other people make decisions that affected me without me having a seat at the table.”

After graduating from Mercer in 2015, Partolan decided to put his dream of going to law school to study immigration law on hold, as the state of Georgia does not allow undocumented people to receive the licensure needed to practice.

Instead, he accepted a full-time position with Asian Americans Advancing Justice-Atlanta, a nonprofit law and advocacy organization centered around protecting the rights of Asian communities in Georgia and the southeastern United States. Partolan spearheaded the organization’s civic engagement program, catalyzing his long-term passion for promoting voting within Asian American communities. He became a prominent figure in the immigration advocacy movement, which put a strain on his relationship with his mother.

“When I first started appearing in newspapers and on television news programs to share my story, my mother, disagreeing with my approach to bettering the conditions for myself and my family, shut me out for several months. We didn’t speak,” he said.

While Partolan’s father, a former activist himself, supported his son’s advocacy, Partolan’s relationship with his parents remained strained as his mother came to terms with the publicity he was receiving, something she warned him against as a child and young adult.

“Over time, my parents’ support only grew. They’d look out for me on TV and record the programs on which I appeared,” he said. “They’d save the magazines and the newspapers that discussed our family’s story.”

Two years ago, Partolan received lawful permanent resident status — two years after his parents. He now looks forward to the day he can cast his first ballot and possibly run for public office.

“People find that funny because my entire job, my career, revolves around voting in elections, and I’ve never cast a ballot in a U.S. election in my life,” he said. “I become eligible for citizenship in about three years, so at that point, I’m going to apply to be a citizen, and I am just so excited for when I get to register to vote.”

Partolan currently works as a national field director for APIAVote, continuing his work mobilizing Asian American voters. He lives in Syracuse, New York, with his fiancee, Marisol, a DACA recipient from Mexico whom he met through their shared experiences and passion for immigration advocacy work, and their 3 1/2-year-old Yorkipoo. They bought their first house together, which Partolan enjoys fixing up and decorating, he said.

Nearly 30 years after his parents made the long journey from the Philippines to the United States, in September Partolan and his family traveled to the Philippines, giving him the chance to meet his extended family and see his birthplace.

“It brought my immediate family closer together and allowed me to deepen my relationship with my parents,” he said. “I saw firsthand why they decided to move our family to the United States and now feel a great deal of gratitude towards them.”

Today, Partolan spends his free time reading, playing video games and spending time outdoors, just as he did as an elementary schooler growing up in the Deep South. Amid a life fraught with change and uncertainty, some things remain consistent and comforting, reflecting Partolan’s goals for his career as an advocate for immigrant communities.

“What I really set out to do was to create an environment where undocumented young people felt supported and empowered,” he said. “As an Asian American, I am powerful, and I and my community have so many things to offer this nation and the world.”

Read more stories of resilience in the Spring 2023 edition of the Global Health in Action Newsletter, and find past editions here.