Jean Sumner, M.D., grew up in rural middle Georgia, in a family of physicians. Her father and grandfather were doctors in Washington County. Her brothers and uncles also took up the family profession. But it wasn’t until Dr. Sumner left home and moved to the adjacent county with her pharmacist husband that she considered becoming a doctor herself.

“When we married and moved, there was absolutely no care,” recalls Dr. Sumner, whose husband opened a pharmacy in his hometown of Wrightsville in Johnson County. “People would come by the pharmacy for advice because they had nowhere to go for care. If they were unable to access the care they needed, the next thing you might hear is they were hospitalized or had passed away. The absolute lack of quality primary care in many rural communities across our state and nation has grave consequences.”

So in 1982, she joined the first class of medical students at Mercer University. When she graduated, she returned to Johnson County and opened the first internal medicine practice in Wrightsville.

“It was a privilege to go home,” recalls Dr. Sumner. “You impact generations of families, and a physician can really make a difference.”

And that’s exactly what Dr. Sumner did for the next few decades. In her years working as a rural doctor, Sumner treated everyone from patients with diabetes and hypertension to those injured working cattle. On rare occasions, women in an advanced stage of labor, about to give birth and in distress, were brought by emergency responders to her office, as she was the only physician in the county for several years.

A new generation of doctors

“Often those in urban areas do not regard rural physicians highly. They think rural care is simplistic and less challenging than other specialties. They believe the weakest doctors go out to rural areas to work,” says Dr. Sumner. “And that’s just not true. Some of the finest physicians I have known are committed to rural health. You really need to be a better doctor with strong clinical judgment.”

But, Dr. Sumner adds, no one person can do it alone, either. Enter Mercer University.

When Mercer President William D. Underwood began his search for a new dean of the Medical School in 2016, he knew exactly who he wanted.

“Dr. Sumner spent decades practicing and speaking about the challenges facing country doctors,” says President Underwood. “She has the experience, and that’s exactly who we needed.”

For her part, Dr. Sumner didn’t need much convincing. “If you live and work in a rural area, individuals or organizations from other areas appear and announce, ‘We’re here to help you.’ And your first thought is, ‘There’s a catch to this,’” says Dr. Sumner. “But if you find out someone has come from Mercer, you know they are there to help and make a difference. That’s meaningful.”

Mercer, says Dr. Sumner, was always committed to finding sustainable solutions in rural health and joining the University was “an honor.”

In a state plagued by a shortage of doctors, aging infrastructure, shuttered hospitals, and more than one million residents without insurance, there was no one solution. But for Dr. Sumner and her team at the medical school, the first step was clear: build a pipeline of rural doctors.

“Our goal is simple,” she explains. “We recruit young people in underserved and rural populations. People who grew up in that environment and treasure it. People who will go back to their hometowns and serve them.”

That kind of recruitment starts long before students apply for medical school. Since being appointed dean in 2016, Dr. Sumner has led the medical school administration in creating numerous partnerships around Georgia in order to reach young people. That includes working with Georgia’s 4-H school programs, where Dr. Sumner and her students share their experiences in middle and high school classrooms.

It has worked. Now, 70% of entering Mercer medical students come from outside the Atlanta metropolitan area, and 50 percent hail from truly rural areas — places with fewer than 50,000 residents per county. But getting students from rural areas through the door was just the first step. The next hurdle was tackling the high cost of a medical education.

She also hosts an annual booth in the “Georgia Grown” building at the state fair. There, Dr. Sumner and current Mercer medical students share information on vaccinations, blood pressure and diet management, and encourage young visitors to consider a path in medicine. Mercer’s medical school also runs a monthly column in the Farmers and Consumers Market Bulletin, a biweekly newsletter distributed by the Georgia Department of Agriculture, and the second-most-read periodical across the state, where students and faculty share information about farmer’s lung, vitamin D deficiency, and other health problems prevalent in rural communities.

Investing in the future

For many Mercer medical students, the desire to serve the state’s rural community was a galvanizing force, but the high cost of med school a prohibitive one. “One of the big challenges was figuring out how to get these young people out of school with a lot less debt,” says President Underwood. “Our goal is to tell them they can be a doctor and create a path for them to get there.”

At Mercer, that path includes a $35 million endowed fund that allows medical school students who commit to rural practice to attend tuition-free.

“Our goal is simple.We recruit young people in underserved and rural populations. People who grew up in that environment and treasure it. People who will go back to their hometowns and serve them.”

Dr. Jean Sumner, Dean of Mercer University School of Medicine

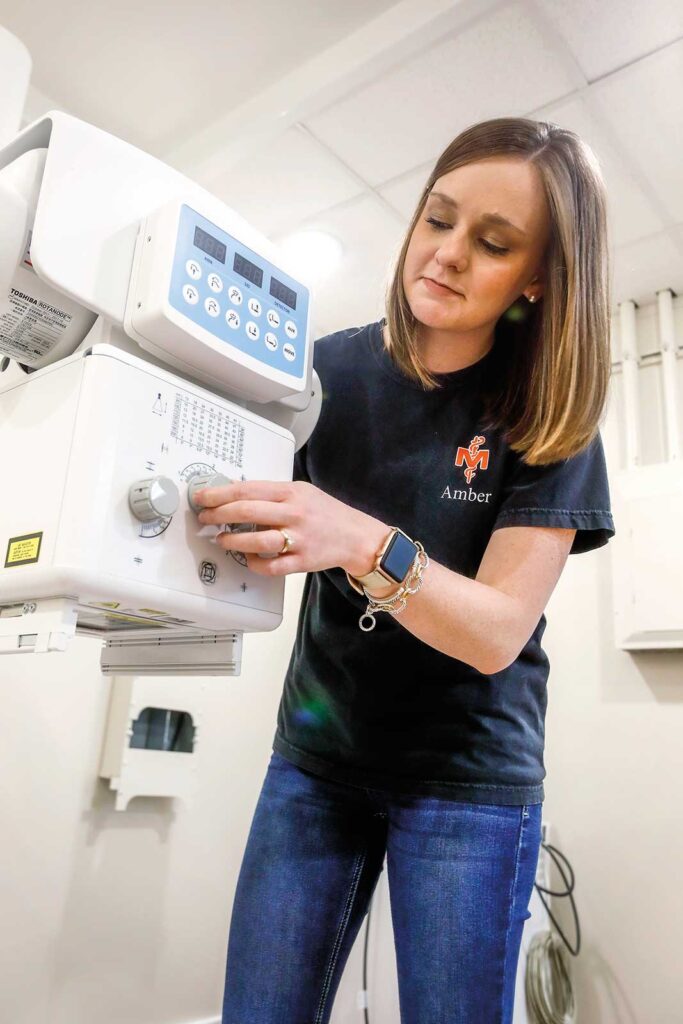

But the opportunity doesn’t end there for students. Creating a network of clinics where students can train in their residency is also part of Mercer’s solution.

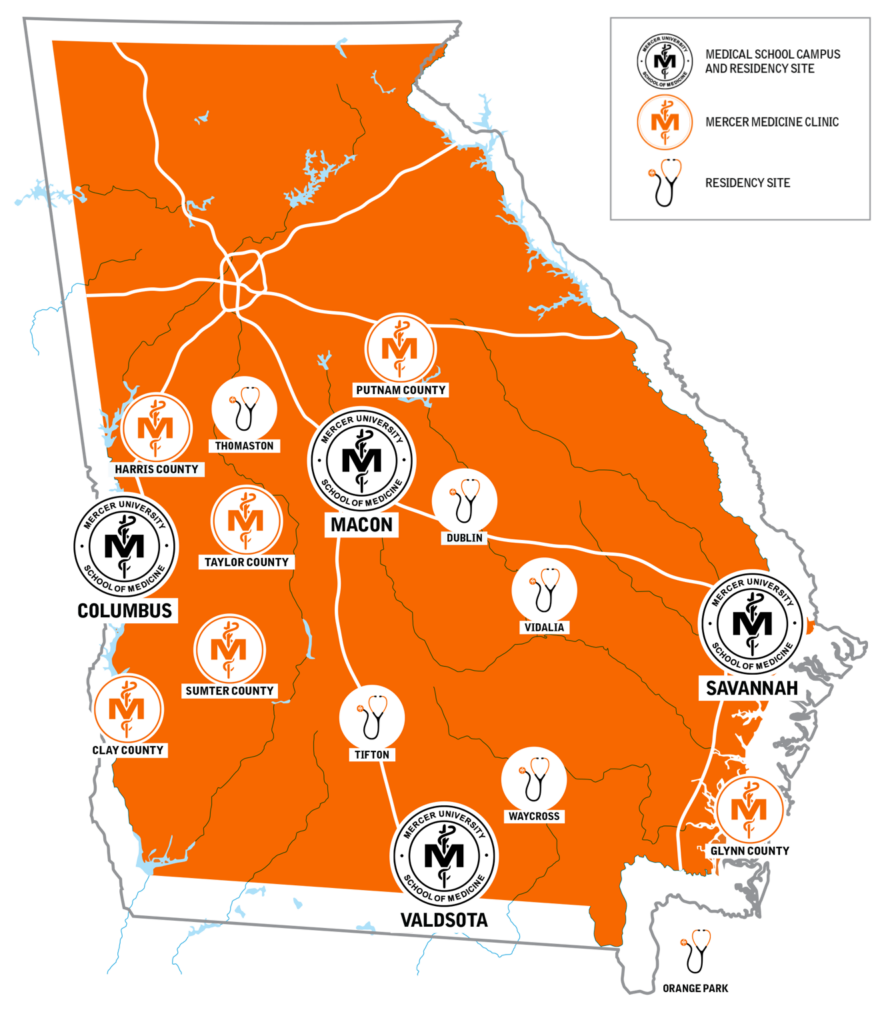

“We want to show that you can provide great service to the community and make a living,” says President Underwood. And while Mercer currently operates six rural clinics, the ultimate goal is to have a clinic within a 45-minute drive from any point across Georgia. “For us, the project starts with finding people who want to be in these rural areas, but it also includes creating a place for them to do their work. That’s part of the package; it’s part of creating capacity in these communities.”

And the work won’t be done, Dr. Sumner says, “until we have a healthy state where no Georgian, no matter where they live, or their station in life, goes without excellent health care. That’s a goal we’re committed to at Mercer, and it’s one that will take all of us.”

Building a network of rural health clinics

It began in 2018 with a phone call. President Jimmy Carter, a member of Mercer’s Board of Trustees, called President Underwood to tell him that Plains had just lost its lone physician. He wanted Mercer’s help in recruiting a doctor to the former president’s hometown in Sumter County.

The School of Medicine did one better. Within three months of President Carter’s phone call, the first Mercer Medicine rural health clinic was up and running with a full-time physician and nurse practitioner, offering comprehensive primary care services. The Sumter County clinic allowed the School of Medicine to pilot the model for replication in other rural communities around the state. Today, in addition to Sumter County, Mercer Medicine has clinics operating in Clay County, Putnam County, Harris County, Taylor County, and Glynn County all medically underserved rural counties. Additional counties are under active consideration.

“The fundamental premise behind these clinics is that folks in rural Georgia put food on our table. They’re the backbone of our state, and they deserve the same access to quality health care as everyone else in the state of Georgia. That’s the mission of our medical school, and these rural clinics represent part of a broad-ranging initiative by the University to transform access to health care in this state,” said President Underwood.

With the growing network of rural Mercer Medicine clinics, combined with the School of Medicine’s four-year campuses in Macon, Savannah and Columbus, two-year clinical campus in Valdosta, and residency programs across the state where future medical doctors are being trained, the transformation is well under way.