Seventy-nine years after a young military pilot bartered some of his belongings in exchange for a human shrunken head in the Amazon rainforest, the ceremonial artifact is returning home to Ecuador.

Until recently, the shrunken head — or tsantsa, as it was known by the indigenous people who prepared it — spent decades at Mercer University. While once on display, the tsantsa was in storage when a team of Mercer researchers learned about it.

They immediately recognized the tsantsa as a valuable artifact but knew the University didn’t have the facilities to display it in a culturally meaningful way.

Tsantsas “were never intended to be items for people to own or possess or gawk at. These aren’t supposed to be curios. This is a human being,” said Dr. Adam Kiefer, distinguished university professor of chemistry. “So we sent it back home so that it can be treated in the appropriate context.”

The researchers — Dr. Kiefer; Dr. Craig Byron, professor of biology; and Dr. Joanna Thomas, assistant professor of biomedical engineering — authenticated and delivered the tsantsa to the Consulate General of Ecuador in Atlanta in 2019, but the COVID-19 pandemic delayed its return to the country.

Plans now are underway to take it back to Ecuador, where it will be recognized with an event upon its return, said Estefhania Hernandez of the consulate.

“Ecuador is so excited about that because we are (getting) back something that is from our aboriginal culture,” she said.

Put on display

Up until the mid-20th century, certain indigenous communities in Ecuador and Peru produced tsantsas from enemies slain in combat using a laborious, multi-step process.

The tsantsas were believed to contain the spirit of the victims and possess supernatural powers that could be transferred to a host’s household during a ceremony, after which the tsantsa had little value to the people. However, in the 19th century Western and European demand for tsantsas as curios drove up their monetary value.

In 1942, U.S. Army Air Forces pilot Jim Harrison was stationed in the Galapagos Islands and on his way to Panama when he was given two weeks leave in Ecuador. He was traveling the interior with a police patrol when he traded military insignia, coins and a pocketknife with a member of the Jivaro tribe in exchange for a tsantsa, according to his memoir.

Harrison went on to graduate school and earned his Ph.D., joining the Mercer faculty as a biology professor in 1962. In 1979, he loaned the tsantsa to director John Huston to use as a prop in “Wise Blood,” a dark comedy that was filmed in Macon.

Dr. Harrison continued to travel and collect artifacts, including pottery. When he retired in 1985, he gave the Sociology Department his collection to display.

“Of all the artifacts he gave us in sociology, the shrunken head was the one he always talked about,” said Dr. Alpha Bond Jr., professor emeritus of sociology. Dr. Harrison would ask, “‘How’s the shrunken head?’ and ‘You all taking good care of the shrunken head?’”

Over time, pieces from the collection were moved and put into storage.

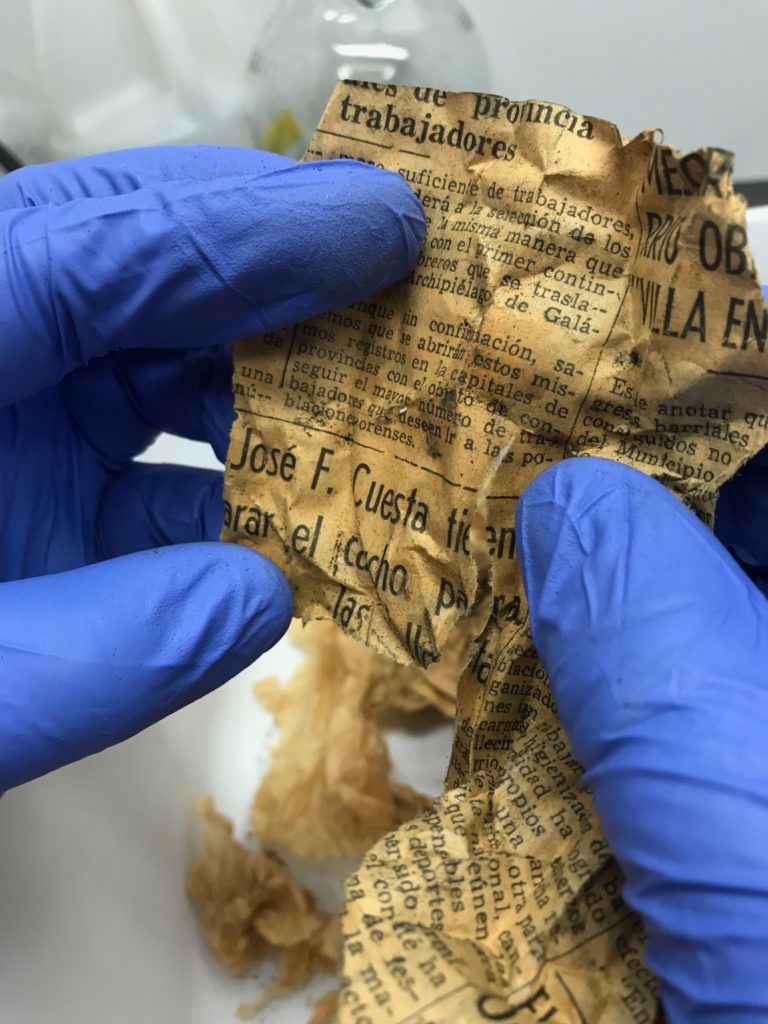

Then, in 2016, Dr. Kiefer and Dr. Byron were clearing items out of the old Willet Science Center to prepare for its renovation when they learned about the tsantsa. The decision was made to repatriate it to Ecuador, but they quickly realized that wasn’t going to be easy.

Because tsantsas had grown in popularity as curios, the demand often outstripped supply, causing an influx of forgeries. The researchers needed to authenticate the tsantsa before they could repatriate it.

‘There’s no playbook for this’

The first thing Dr. Byron and Dr. Kiefer did was contact the Ecuadorean embassy in Washington, D.C. The embassy connected them with officials from Ecuador’s National Cultural Heritage Institute, which provided the required criteria for repatriation, but the researchers had to figure out how to authenticate it from there.

“There’s no playbook for this. We had to come up with our own,” Dr. Kiefer said.

They brought on board an undergraduate chemistry student, Amy Jenkins, who read peer-reviewed literature on the topic and came up with a list of 33 characteristics that would indicate the tsantsa was authentic. The characteristics were broken down into four categories: skin, structure and facial anatomy, evidence of traditional fabrication, and hair.

In looking at the criteria, they realized that some were difficult to evaluate without a CT scan. Dr. Thomas got involved and reached out to a biomedical engineering alumnus with connections to MD Anderson for help.

The tsantsa was scanned at Baptist MD Anderson Cancer Center in Jacksonville, Florida. Using the CT scan, Dr. Thomas created a 3D rendering, which allowed them to examine the tsantsa without the hair.

“Some of the evidence is really obscured by the hair, and in an effort to handle it delicately, really being able to have a 3D rendering that came from the CAT scan allowed us to look at layers of it,” Dr. Thomas said. “You can look at it from the inside out. We can digitally take the hair off and look at what’s remained, and that really helped solidify several of the critical points.”

Researchers were able to hold the 3D model in their hands, the way the person making the tsantsa would have.

“You can see the opening in the hole of the head where the original string was, and you can see the incision made down the back of the neck. You can see the morphology of the ears,” Dr. Kiefer said. “You can see so much of this just from holding it.”

Dr. Thomas shared the file for 3D printing on a scholarly website that collects 3D data from natural history, cultural heritage and scientific collections. Going forward, 3D models of the tsantsa could be used in museums or as tools for teaching students the features of a ceremonial tsantsa.

“They’re not having to handle an original artifact, but they’re still learning the identification process and the morphology of genuine artifacts versus fakes,” she said.

Ultimately, the Mercer tsantsa met 30 of the 33 indicators. The researchers submitted a formal report to Ecuadorean officials, who declared it an authentic tsantsa, Dr. Byron said.

The researchers have since authored a study describing the authentication and repatriation, which was published May 11 in the peer-reviewed journal Heritage Science.

The study not only highlights the technical tools and methods Mercer researchers used in the authentication of the tsantsa but also allows other universities with culturally significant artifacts to recognize that repatriation is an option, Dr. Kiefer said.

‘Where it belongs’

Museums around the world have been taking hard looks at their collections in recent years, with many committing to returning culturally significant items to the countries from which they were taken. The items may range from pieces of art to tools or weapons to human remains.

In the U.S., the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act provides for protection and repatriation of certain cultural items, including human remains.

Dr. Byron, who has a background in anthropology, said he viewed the tsantsa through the lens of that law.

Repatriation of the tsantsa “was important to me because I just knew that repatriation was the standard in the world of anthropology and this object should be treated that way,” he said.

Through this process, Dr. Thomas said she learned what tsantsas meant culturally to the people who made them, and she’s glad to see the shrunken head returned to Ecuador.

“The good news is we know that the government of Ecuador now has this, and they are the ones now who get to make the decision as to where it belongs,” Dr. Kiefer said.