MACON – A team of Mercer University researchers authored a newly published study that describes the authentication and repatriation of a ceremonial shrunken head to Ecuador.

The ceremonial tsantsa – or shrunken head – was returned to Ecuador in 2019 after being discovered among stored exhibits on the Macon campus.

A team of researchers at Mercer – led by Dr. Craig Byron in the Biology Department, Dr. Adam Kiefer in the Chemistry Department and Dr. Joanna Thomas in the Department of Biomedical Engineering – co-authored “The authentication and repatriation of a ceremonial tsantsa to its country of origin (Ecuador),” published today in the peer-reviewed journal Heritage Science. Mercer alumni Sagar Patel, Amy Jenkins and Anthony Fratino are also among the article’s seven co-authors.

Tsantsas are unique and valuable artifacts that were produced by the Shuar, Achuar, Awajún/ Aguaruna, Wampís/Huambisa, and Candoshi-Shampra (SAAWC) peoples until the mid-20th century. They were made from the heads of enemies slain during combat in a labor-intensive, multi-step process.

Tsantsas became valuable as keepsakes during the 19th century as Western/European cultural encroachment into the Ecuadorean and Peruvian interior prohibited their manufacture. This unmet demand resulted in the production of convincing forgeries. As a result, repatriation of tsantsas to their places of origin requires prior authentication.

The ceremonial tsantsa discovered at Mercer was described in the personal memoirs of the original collector – a deceased faculty member – as having originated in the Ecuadorean Amazon.

Dr. Kiefer and Dr. Byron contacted the Ecuadorean Embassy to the United States, who in consultation with the National Cultural Heritage Institute of Ecuador provided guidance on how to authenticate the tsantsa, a requirement of its repatriation to Ecuador.

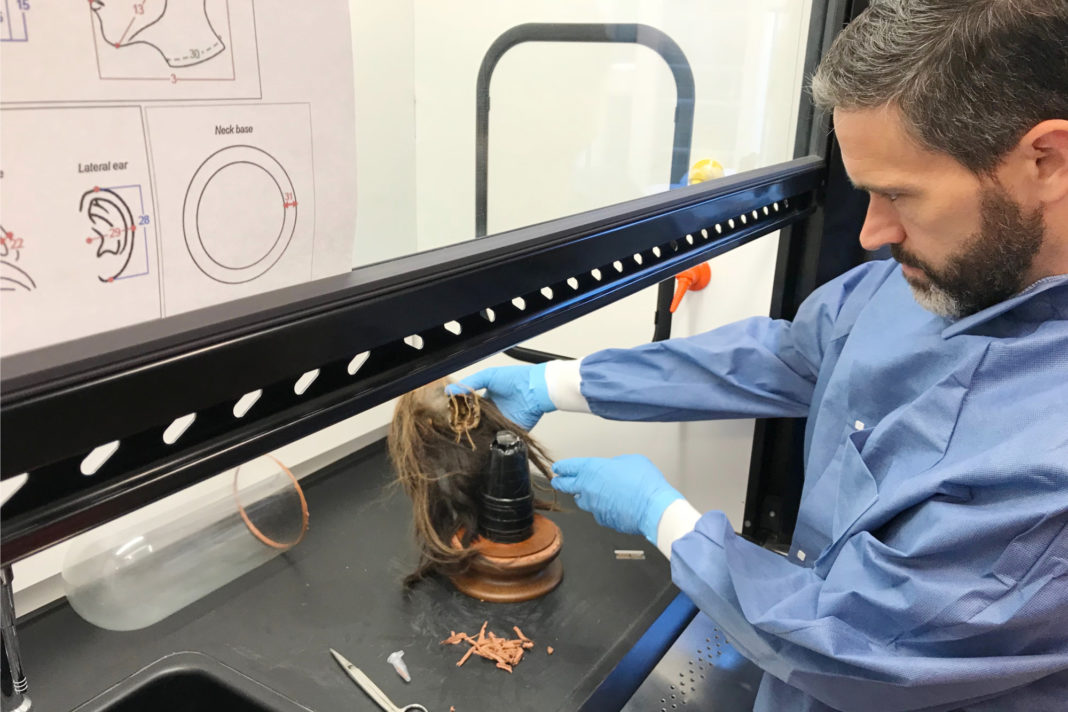

The researchers developed a list of criteria for authenticating a tsantsa from this guidance and the academic literature, and they further examined the anatomy of the tsantsa using computed tomography (CT).

They found that the tsantsa had the structural hallmarks of a ceremonial artifact, such as the size of the head, which was about as large as an adult human fist, and three holes in the upper and lower lips, joined together with a vegetal fiber, which are common in other ceremonial examples. The tsantsa also showed a distinctive, three-tiered hairstyle consistent with hair worn by SAAWC peoples.

In total, the researchers were able to affirm 30 of 33 authenticating indicators, including evidence of traditional fabrication and modification.

While the authors caution that some of the authentic tsantsa characteristics might have been damaged while being used as a prop in the 1979 John Huston film “Wise Blood,” their findings allowed them to conclude that the artifact was a genuine, ceremonial tsantsa and not a forgery. The results of the authentication were accepted by the Ecuadorean government, and the tsantsa was repatriated in June 2019.

The researchers also produced a to-scale 3D replica of the tsantsa, suggesting that 3D-printed reproductions may be useful as enhancements, and in some cases even replacements for, authentic artifacts in cultural and historical education.