Dr. Kedrick Hartfield didn’t set out to be an educator.

“Teaching was at the bottom of the list of things that I wanted to do with my life,” he said. “It was right below going into a branch of the military and right above being a lifelong criminal.”

But God, he said, had different plans.

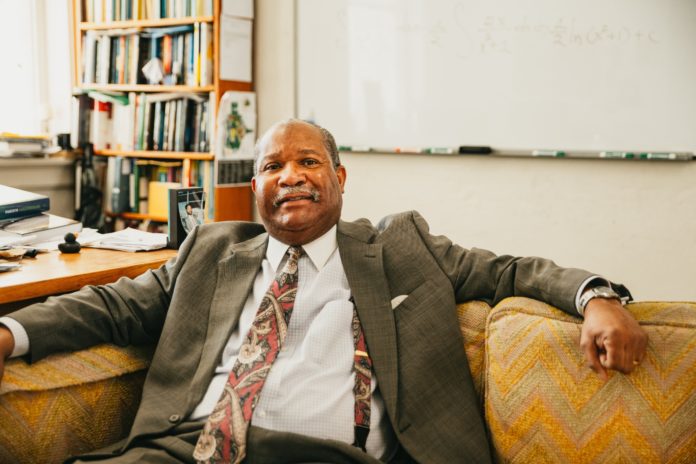

Dr. Hartfield is now a professor of mathematics and has taught at Mercer University for 40 years, which makes him the longest-serving Black professor at the University. He also is the longest-serving full-time faculty member in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

“It was as if somebody had turned me on to a drug that I became addicted to,” he said about his first teaching experience in graduate school, where he begrudgingly became a teaching assistant. “This must have been God’s calling for my life because I would not have done it had I not been forced into it.”

Once he started teaching, he found the experience of getting students to understand a concept with which they struggled very gratifying.

“There is nothing like understanding. That is more valuable than silver or gold,” he said. “And to have someone understand something which they previously did not is just rewarding.

“And that’s why I fell in love with teaching.”

A strong work ethic

Growing up in Augusta, Dr. Hartfield first became interested in mathematics before he even entered kindergarten.

“My older female cousins babysat my brothers and myself, and I was just naturally curious watching them do their homework,” he said. “I mean, they didn’t have a lot on television back in the early ’60s that interested a child … so you had to pass the time, and when they were doing their homework, I would sit around and talk to them.”

By the time he entered grade school, he already could count by fives and tell time on an analog clock, much to the disbelief of his teacher, who spent an hour and a half of class quizzing him and trying to trip him up.

Dr. Hartfield continued his schooling, earning a Bachelor of Science degree from Augusta College (now known as Augusta University), where he majored in mathematics and minored in biology.

By the time he graduated in 1979, the country was coming out of a recession, and unemployment was high. Dr. Hartfield went down to the unemployment office and put in his resume to try to find a job.

He was chosen to interview for four positions: gathering money from vending machines, working on a farm, collecting trash and serving as a high school janitor.

“Those were my four job offers, and they hurt my pride so much,” he said. “I just went through four-plus years of college, majoring in mathematics, minoring in biology, with most of my electives in physics and chemistry.

“I didn’t need a college degree to do any one of these jobs.”

He turned them all down.

“So, I said, ‘You know what I’ll do? I’ll go back to school and get a master’s. Hopefully the economy will be better, and I can find a job,” he said.

He then enrolled at the University of Georgia, studying mathematics. He was tutoring students for free when a professor offered him a job as a teaching assistant.

“I’m here at Mercer and I have a Ph.D. because I won’t let people outwork me.”

Dr. Kedrick Hartfield

Dr. Hartfield bristled. After all, he didn’t have any experience in education.

But the professor persisted.

“He said, ‘You’ve got all the potential to be a very good teacher because you’re patient and you repeat things,’” Dr. Hartfield recalled.

Still, he turned the job down a few times before finally accepting.

“The only reason I accepted that TA position was because the money that I had saved up was running low,” he said. “But it turned out to be something I thoroughly enjoyed.”

After graduating with his master’s degree and passing his exit exams, the head of mathematics told Dr. Hartfield about a job opening at Mercer. He applied to the University and several other colleges and was offered a job at each one.

Mercer didn’t make the best offer, he said, but it kept him close to his aging parents in Augusta.

“If something happened or one of them got sick, I wanted to be able to get there in two hours or two and a half hours,” he said.

So, in 1981, at the age of 25, Dr. Hartfield started his career at Mercer as a visiting instructor.

“I was only supposed to be here for one year, but at the end of that first year, the math department held a meeting, unknown to me, and decided that they liked the job I was doing and offered me a permanent position as an instructor, and I accepted it,” he said.

In 1993, he began working on his Ph.D. at the University of Georgia, graduating with his doctorate in mathematics in 2002. His research focused on the Rule of Three, which is the act of presenting functions from a symbolic, graphical and numerical point of view and determining which perspective best facilitated understanding.

Now a full professor with tenure at Mercer, Dr. Hartfield is as dedicated as ever to helping students understand math.

“In mathematics, and I guess as with most subjects, one size does not fit all. So explaining it one way may, let’s say, allow you to have 99% of the class understand the material,” he said. “But what about that 1%? I’m not willing to write them off, so I’ll try another method.”

He often invites students to join him during office hours and have them work problems on two big white boards in his office. He stresses to them the importance of doing the work as the key to succeeding in his class.

Students without a natural affinity to math might have a harder time, but they can learn the content and get a good grade if they do the work, he said.

“Usually, the more people work, the more their understanding develops,” he said.

He learned the importance of a strong work ethic from his father.

“My father did always say, ‘Let nobody outwork you. Don’t fail because of your lack of work ethic. That’s something you can control. You can’t control how much intelligence God gave someone else. But you can control your own work ethic,’” Dr. Hartfield recalled.

“I’m here at Mercer and I have a Ph.D. because I won’t let people outwork me.”

‘What is going on?’

When Dr. Hartfield first came to Mercer in the early ’80s, he was one of four Black faculty members on campus.

He said he often found himself encountering people who did not believe he was a faculty member.

Dr. Hartfield recalled a time in spring 1982 when a Mercer police officer questioned his presence in the student lounge, where he often would go to watch the news or review his notes before his 8 a.m. class.

When Dr. Hartfield told him that he was a faculty member, the officer “whipped out his walkie talkie on the side of his hip, so close to my face, I felt the breeze. He invaded my space.

“He called in the walkie-talkie. He was only centimeters from me. He said, ‘Do we have a faculty member here by the name of Hartfield?’ And it was a Black female on the phone because I recognized her voice, and she said, ‘That’s a big 10-4.’ He put the walkie talkie back on his side hip, turned around and walked out.”

The officer never apologized, and Dr. Hartfield never reported it. He said at 26, he was jaded about race in America and decided he would just let it run off his back.

But “that couldn’t happen today because (Mercer Police) Chief (Gary) Collins would know about it, so would the provost and the president,” he said.

In another incident that year, the young instructor was walking across campus when a Mercer police officer stopped him and asked to see his ID.

“It was just one incident after another. I said, ‘What is going on here?’” Dr. Hartfield recalled.

He thought about his father’s advice to look at all possible remedies before calling someone a racist or a bigot.

“So I said, ‘You know what? I’m going to start wearing a suit and a tie and suspenders, dress shoes,’” he recalled.

He cut his afro low and shaved his beard close to his face.

“I’m going to be as presentable and non-threatening as I can to white people — faculty, students, whatever — and I’m going to see if that’s going to minimize a lot of this, and it did minimize a whole lot of it. Not all of it, but it did minimize a lot of it,” he said.

“And I have worn suits every day since.”

Since that time, Mercer has made great strides enrolling students who are representative of the state’s diverse population, Dr. Hartfield said. And while the University has made progress in terms of gender diversity among faculty, he said, it has only improved marginally when it comes to hiring Black faculty members.

“I remained at Mercer because I loved teaching and hoped the faculty would eventually become more diverse,” he said. “I still have hope after 40 years.”

Dr. Chinekwu Obidoa, an associate professor of global health studies, said she respects the way Dr. Hartfield has represented himself as a Black faculty member.

“A lot of time, people don’t see what that means or how much responsibility a faculty member of color carries because embodied in your body is everything Black,” she said. “And any mistake you make, any comments you make, are not only attributed to you but are attributed to your race. …

“That diversity work is the kind of work that people of color have to perform just by being a person of color in a space.”

Dr. Hartfield has been a role model for countless students and played an important role in making Mercer the University it is today, Dr. Obidoa said.

“Part of his work is also part of why we have retention of Black students. We have so many students of color in the math department and all over,” she said.

A positive role model

Mercer’s diverse student population is in part attributed to the University’s Upward Bound program, which started in 1966 and serves as a pipeline to Mercer for Black students.

Dr. Hartfield started teaching in the summer program in 1982 and has taught every year since.

“Most of the students at Upward Bound are people of color, and it is really important that young people of color have some positive role models beyond what they see on television and movies or read about in newspapers,” he said.

In class, he taught high school students the math they would see in school their upcoming year. But outside of class, he imparted life lessons.

He said he talked to young men about “how they should dress, how they should conduct themselves, how they should act — if they haven’t been talked to by a parent — when they are pulled over by policemen.”

Dr. Keith Howard, a professor of mathematics and interim dean of graduate studies at Mercer, was a rising senior in high school when he found himself in Dr. Hartfield’s precalculus Upward Bound class.

Dr. Hartfield “was someone who did not play around with certain things,” Dr. Howard said. “He believed in accountability, and so, a lot of my colleagues viewed him with fear, but to me, he was an example because the standards that he held for you were the same standards he held for himself.

“And so you could tell that he was really trying to grow you into something that he truly believed you could become.”

Dr. Hartfield cares about his students and pushes them as far as they can go, Dr. Howard said.

“Regardless of what your natural abilities are or what your baseline performance level is coming in, he wants to see you grow, and he wants to see you putting forth the effort to make that growth,” Dr. Howard said. “He wants to see growth, and he wants to see your work ethic.”

And he’ll be with the student every step of the way.

“The amazing thing is he’s willing to take that walk with you,” Dr. Howard said. “One thing, and this was true when I was an Upward Bound student, and it’s true today, he is very generous with his time outside of class to help you in those efforts.”

After Dr. Howard graduated high school, Dr. Hartfield stayed in touch and was a great encouragement — even after learning Dr. Howard wanted to pursue a career in engineering rather than math.

“Dr. Hartfield, when he heard about my plans, he was really agreeable to them, but he kept telling me, ‘It’s a shame to waste that amount of mathematical talent,’” Dr. Howard said.

In pursuing dual bachelor’s degrees in math and engineering, Dr. Howard found he enjoyed the math portion more. Dr. Hartfield encouraged him to look at possible careers in mathematics, urged him to consider going to graduate school and told him about jobs available at Mercer.

“Whenever there was an opening here, he would let me know about it and encourage me to take part in it,” Dr. Howard said.

Because of Dr. Hartfield, countless students who may have struggled in math were able to successfully fulfill their math requirements, said Dr. Chester Fontenot Jr., professor and director of the Africana studies program at Mercer.

“He has the ability to relate to students and take material that can be difficult at times and present it in such a way that it becomes accessible to undergraduates, which is in itself a real gift,” Dr. Fontenot said.

But not only is Dr. Hartfield a good teacher, he’s also a strong man of faith, a family man and a good friend.

“He’s one of the few people I’ve met in my life that I’m glad that I was able to get close to,” Dr. Fontenot said.