Bill Westwood was a junior at Mercer University in 1965 when he received a C in a design course. He was indignant. Up until then, he had never gotten anything lower than an A in art.

He went to the professor’s office to complain. They ended up talking about art careers, and she asked if he had ever considered medical illustration, given his desire to create realistic art in an era that valued more abstract and expressionistic styles.

Westwood now admits the C was deserved. But the conversation it prompted was a turning point in his life.

Until then, “I didn’t see a way to make a living in art,” said Westwood, who graduated from Mercer with a Bachelor of Arts in English literature in 1967. He double-minored in art and biology. “I had never heard of medical illustration. I had no clue what it entailed.”

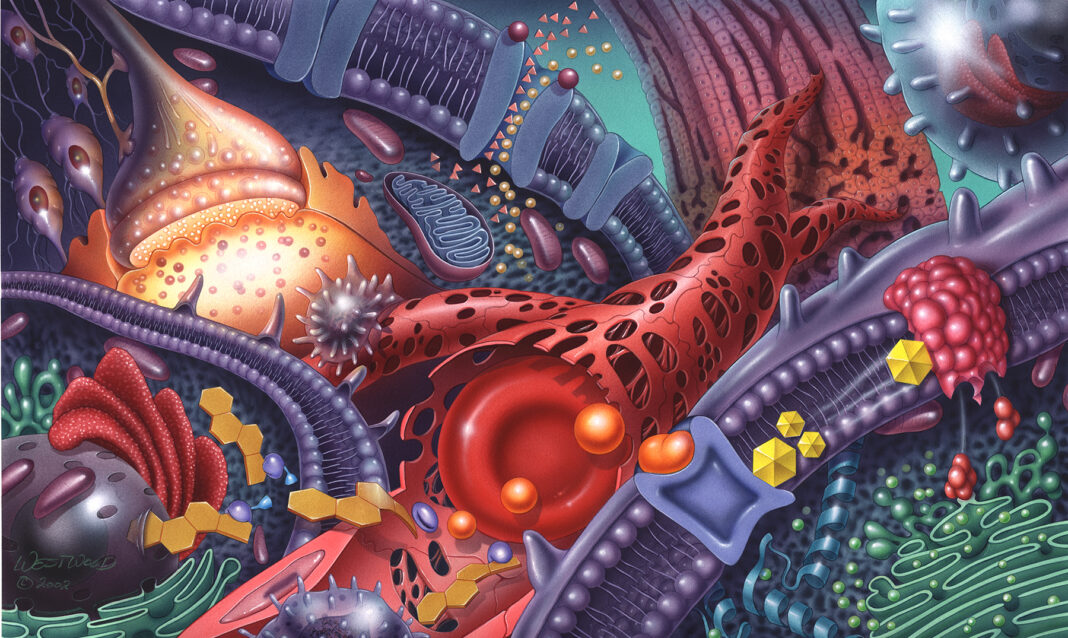

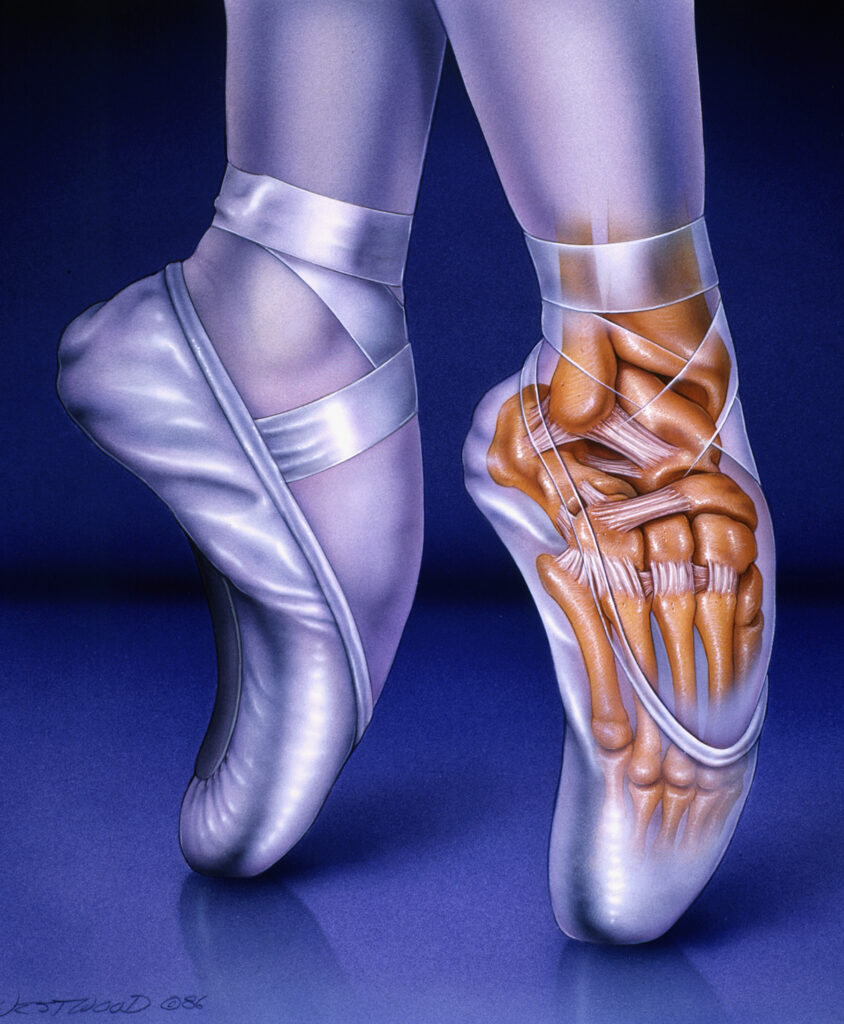

But as he looked into the field, which uses art and science to create accurate visual representations of complex medical concepts, he realized he had found his career.

For over five decades now, Westwood has been a board-certified, award-winning medical illustrator and mentor for others in the field. Now 80, he still has a hard time thinking about retiring.

“Every day is a new challenge. Every project is a new challenge,” he said from his studio in downtown Albany, New York. And “the painting part is actually a lot of fun.”

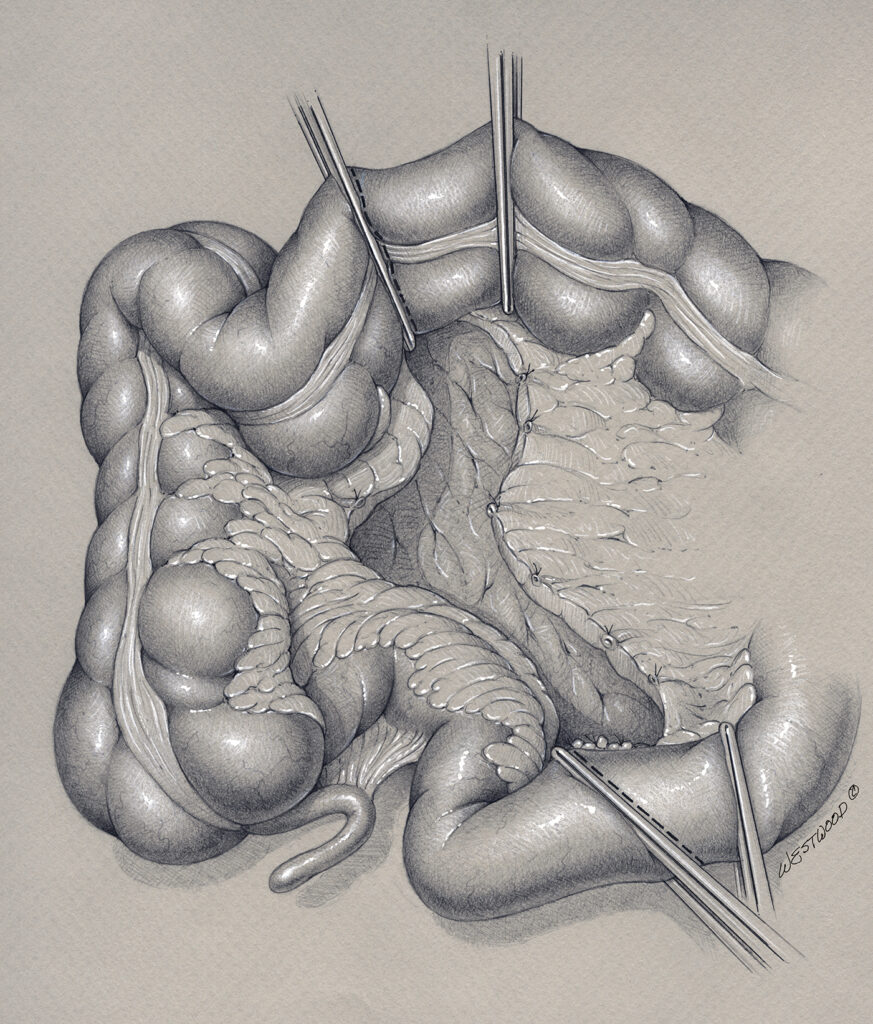

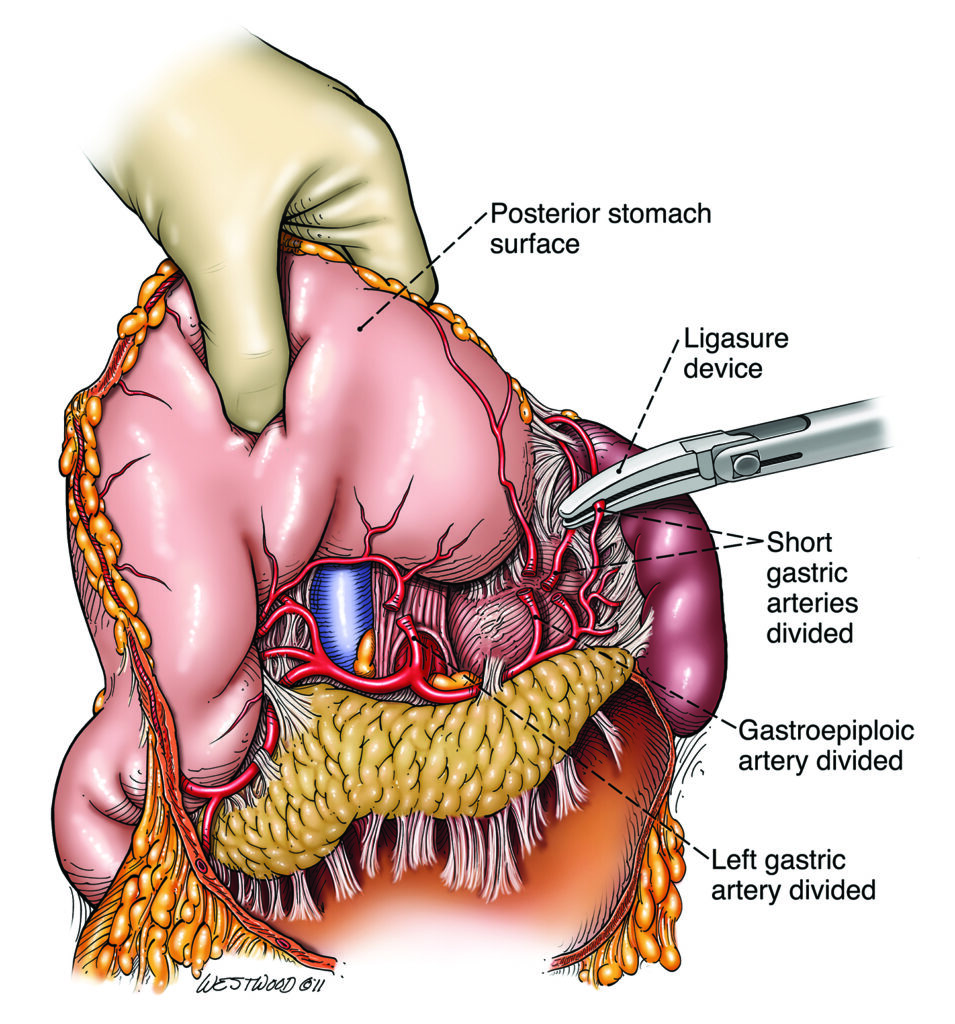

Surgical illustration

After graduating from Mercer, Westwood was accepted into the three-year graduate medical illustration program at the Medical College of Georgia (now Augusta University).

He studied alongside medical students in classes like human anatomy, pathology, genetics and surgery, in addition to taking advanced illustration courses. The Vietnam War draft interrupted his schooling, and after serving two years in the Army, he received his master’s degree in medical illustration in 1972.

Westwood began his career as a medical illustrator at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, working with surgeons to illustrate complex medical procedures.

For one project, he worked with surgeons to illustrate an improved transnasal approach to pituitary tumor surgery. His role was not only to show the procedure but also develop strategies to change the perception of the process among neurosurgeons. To do this, he sat in on dozens of surgeries and attended rounds to fully understand the procedure and objections to it.

The result was a 50-foot exhibit that addressed those criticisms and illustrated the procedure using life-sized wax models and line art to show each step. The center of the exhibit incorporated a working operating microscope for surgeons to view and use instruments to probe a model of an exposed pituitary tumor.

The exhibit won numerous awards, including a Billings Gold Medal from the American Medical Association in 1977. Westwood also was a co-author on the exhibit and published papers about the procedure.

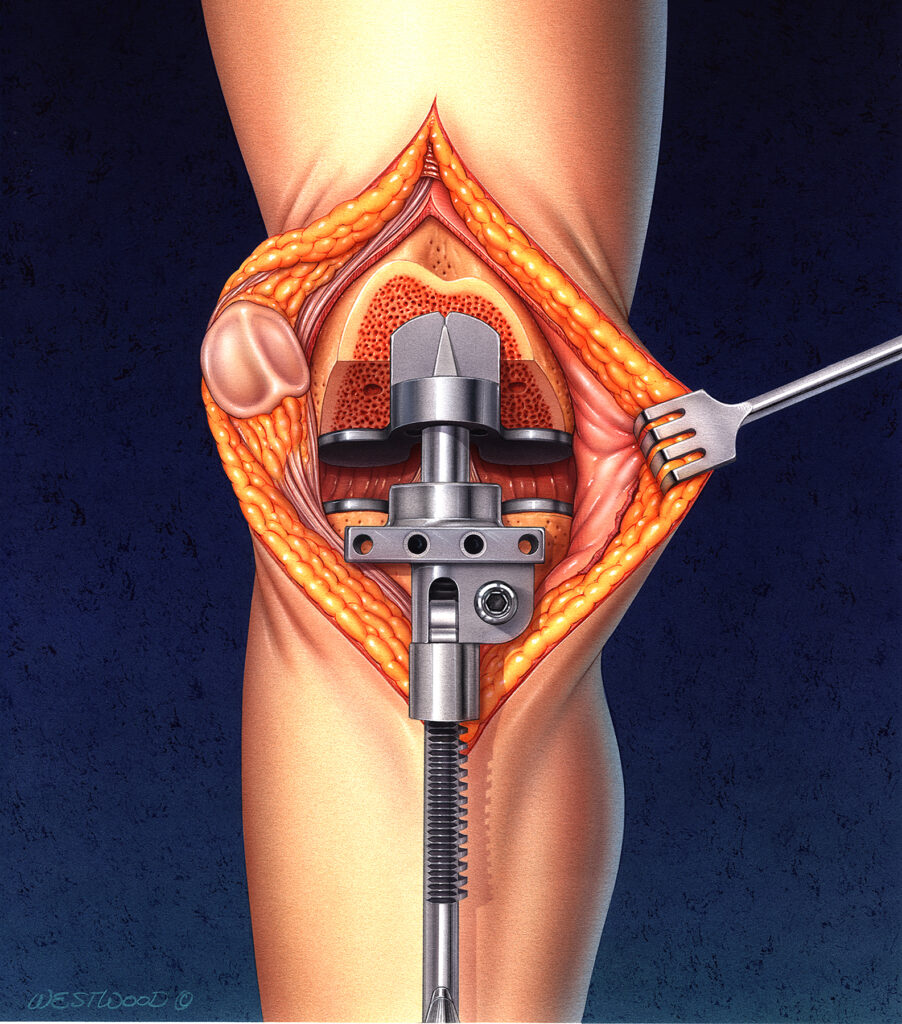

A lot of work goes into illustrating a surgical procedure.

“I really do a lot of research on the procedure, so I have a thorough understanding of what’s going to happen,” he said. “If understanding the procedure required it, I would typically stand on a platform behind the surgeon and peer over their right-hand shoulder, and I would either make little thumbnail sketches, or I would take quick photographs to help me recall complex maneuvers.”

Back in his studio, Westwood figures out how to show the surgery in a limited number of images.

“Part of what you do as a surgical illustrator is visual editing. You can’t illustrate every step in an entire three- or four- or six-hour procedure,” he said. “It requires you to fully understand the anatomy involved and each surgical step. You then edit it down and put it into a series of steps that a surgeon can use to educate others so that they can utilize that understanding to perform the procedure.”

Breaking into new markets

In 1982, after 10 years at the Mayo Clinic, Westwood left to start his own business. At the time, there were few self-employed medical illustrators, and he became part of a movement to open up editorial and advertising markets for medical illustrators nationwide.

“At that time, markets beyond the textbook market for medical art just didn’t exist. Nobody outside of the textbook business and institutional individuals knew anything about medical illustration,” he said.

Advertising agencies typically hired commercial illustrators who didn’t know anything about medicine, anatomy or surgery and would frequently get illustrations wrong. But because the agencies hiring them didn’t know any better, they didn’t get called on it, he said.

Westwood conceived and created the Medical Illustration SourceBook, a directory featuring the work of self-employed medical illustrators. The first edition was mailed to thousands of medical advertising agencies, pharmaceutical companies and medical journals.

“All of the sudden, people in the agencies became aware of what a medical illustrator could do,” he said. The Medical Illustration SourceBook is now in its 38th edition.

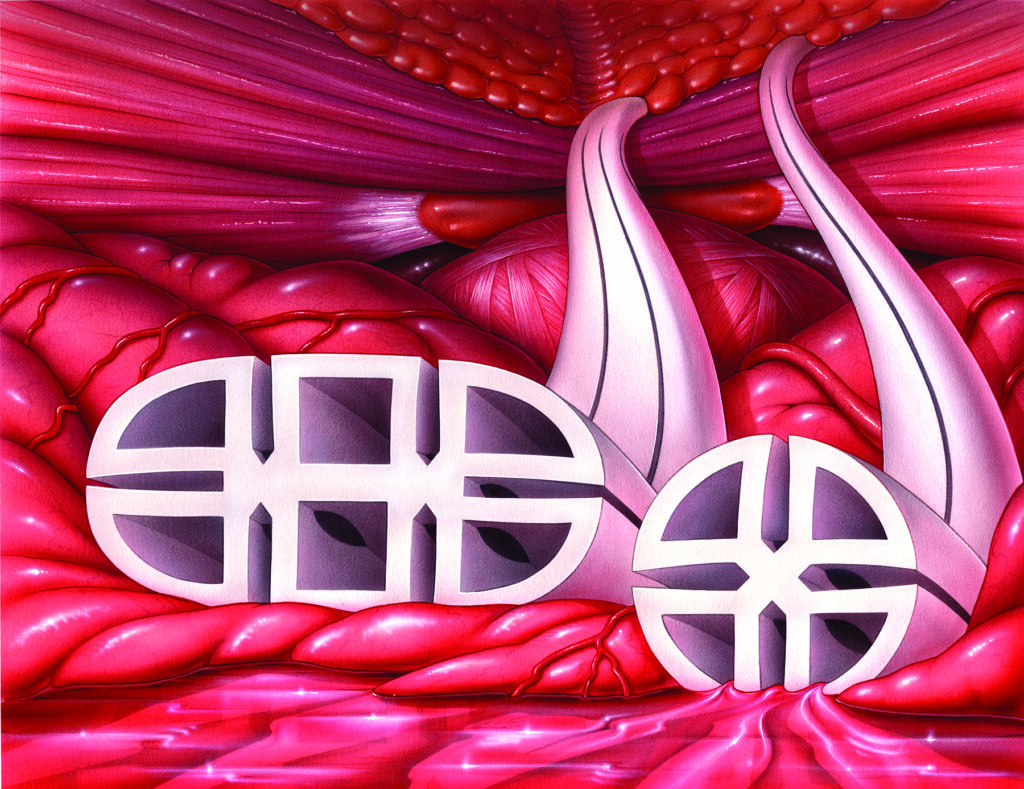

While realistic, medical illustration is also a creative endeavor that can be approached in a variety of ways depending on the audience. For example, if Westwood is creating an illustration for a medical magazine cover, it may be more conceptual.

“You’re not looking to show anatomy the way you show it in a textbook. You’re not teaching anything,” he said. “You want it to be accurate, but you also want it to be visually interesting enough, so if it’s sitting in the center of a medical library on the shelves with other medical journals, somebody’s going to see the cover and be interested enough to at least pick it up and look at it.”

He might approach an illustration inside the magazine differently.

“To illustrate some more technical aspect of an article, those illustrations would be more like teaching illustrations for textbooks,” he said.

The tools he uses to create medical artwork have changed over the years. In the beginning, he used carbon dust and pen and ink. When he started commercial work, he began to use watercolor, gouache — a type of paint — and airbrush.

“What I do now is make a pencil sketch, and I will scan that into the computer, and I’ll paint it electronically in Photoshop, similar — in a way — to how I used to paint that same sketch with an airbrush and watercolor,” he said.

Westwood now primarily works on medical legal cases, in which he illustrates a person’s injuries for an attorney to present to a jury at trial.

“A lot of times people who have been injured might be sitting in the courtroom, and to a jury, they look OK. But they went through weeks, months and sometimes even years of unseen pain and suffering trying to deal with their injuries and recovering from surgeries required to repair those injuries,” he said. “After reading and understanding all of their medical records, such as radiology reports and operative reports, I will create a series of anatomical and surgical illustrations that will help the attorney explain to a jury and to a judge how this individual was injured.”

Westwood’s medical artwork has won 38 national awards and six Max Brödel first place awards for surgical illustration from the international Association of Medical Illustrators. He has held several leadership positions with the Association of Medical Illustrators, including as president on the Board of Governors, and in 2010 he was awarded the organization’s Lifetime Achievement Award.

He currently is working on about a dozen projects for his business, Westwood Medical Communications, and is an adjunct assistant professor in the medical illustration program at Augusta University.

Feature photo: Medical illustration by Bill Westwood. © Westwood All rights reserved.