Tucked inside an exclusive golf club on St. Simons Island, shaded by live oak trees draped in moss, lie about 100 graves of the enslaved and their descendants.

Accessible only to those with relatives buried there, Retreat Cemetery strands in contrast to the nearby fairway where golfers play.

For the past several years, Mercer University students have been learning the stories of African Americans buried at Retreat and elsewhere on the island. In doing so, they are helping preserve the history of a disappearing community in Coastal Georgia.

As part of Dr. Melanie Pavich’s special topics course, “History of African Americans in Coastal Georgia,” students in the College of Professional Advancement interview elders from the Gullah-Geechee community and create digital stories to share and archive.

“We’re working against the clock in terms of trying to get as many oral histories as we can trying to build this archive,” said Dr. Pavich, associate professor of history and interdisciplinary studies in the College.

The Gullah-Geechee people are descendants of Africans enslaved on rice and cotton plantations in coastal areas of the Southeast. This included Georgia’s Golden Isles, which grew in wealth because of the work of enslaved Africans.

The Gullah-Geechee have their own distinct language, culture and foodways that were passed down from their ancestors. While they once made up most of the population in areas like St. Simons Island, their numbers now are dwindling.

“One of the things that’s happened on St. Simons and other places in Coastal Georgia is that these people from the Black community there — the majority of whom can trace their ancestry back to enslavement — have been squeezed off the island because of development,” Dr. Pavich said. “Some have died off, but many of the people … have just been squeezed off the island.”

Henry “Chip” Wilson, 69, has lived his whole life on St. Simons. He can trace his family’s history on the island back to 1849, before the Civil War, when his great-grandfather was enslaved on the Harrington Plantation.

Wilson has seen firsthand the encroachment of development on these historically African American communities.

“Most of the families here in this area have been being taxed out of the land since — oh goodness, — ’94, ’95,” he said.

Wilson, who has been interviewed by several Mercer students for the project, said he thinks it’s great that they’re helping to preserve St. Simons’ African American history:

“How do you know where you’re going, if you don’t understand where you came from?”

Discovering African American history

Dr. Pavich’s class is taught over two eight-week sessions. Students spend the first eight weeks learning about the history of African Americans in Coastal Georgia by reading, watching films, writing papers and researching. They also learn how to conduct an interview.

Typically, between the two sessions, the class takes a three-day weekend trip to St. Simons to tour the area and conduct interviews. The trip didn’t happen this year due to the COVID-19 pandemic, so students interviewed the elders over the phone or Zoom.

During the second session, students transcribe their interviews and produce digital stories based on what they learned. At the end of the course, the students usually present their digital stories as part of a public program on St. Simons Island, although the pandemic prevented them from doing that in the spring. A presentation of their work is now planned for October.

The project and public programs have been supported by seed grants from Mercer’s Office of the Provost as well as grants from Georgia Humanities and Mercer’s Center for the Study of Narrative.

The yearly programs have brought together diverse communities on St. Simons Island and have connected Mercer students with guest speakers such as Dr. Daina Ramey Berry, professor and chair of the History Department and Oliver H. Radkey Regents Professor of History at the University of Texas at Austin.

“It’s been really wonderful because it has allowed this broader view and brought much more attention to the importance of African American history, not just in Coastal Georgia but even throughout the state,” Dr. Pavich said.

Uncovering the past

The class works with the St. Simons African American Coalition, which helps identify elders to interview and displays the students’ digital stories in the Historic Harrington School. The stories, including interview transcripts, photos and videos, are also archived at Mercer and will become part of URSA: University Research, Scholarship and Archives at the library.

The Harrington School, a one-room schoolhouse, was built in the 1920s and served as the main school for three African American communities on St. Simons until desegregation in the 1950s. Today, it serves as the home base for the coalition.

“The class normally gives us a digital story, and sometimes we play them when people come into the Harrington School. We play the digital stories, so they can hear for themselves what happened,” said Amy Roberts, executive director of the coalition.

Past stories have included interviews of people who attended the Harrington School.

“They talk about the years that they were in school there and things that happened,” said Roberts, who also went to the school. “So they get to learn more about what happened at the Harrington School and in the African American community on St. Simons.”

Most recently, students have focused their research on African American cemeteries on St. Simons, including the Retreat Cemetery on the former Retreat Plantation, one of the preeminent plantations on the island.

“If you can trace your ancestry back to enslavement on that plantation then you can still be buried in that cemetery, and people continue to be buried there,” Dr. Pavich said.

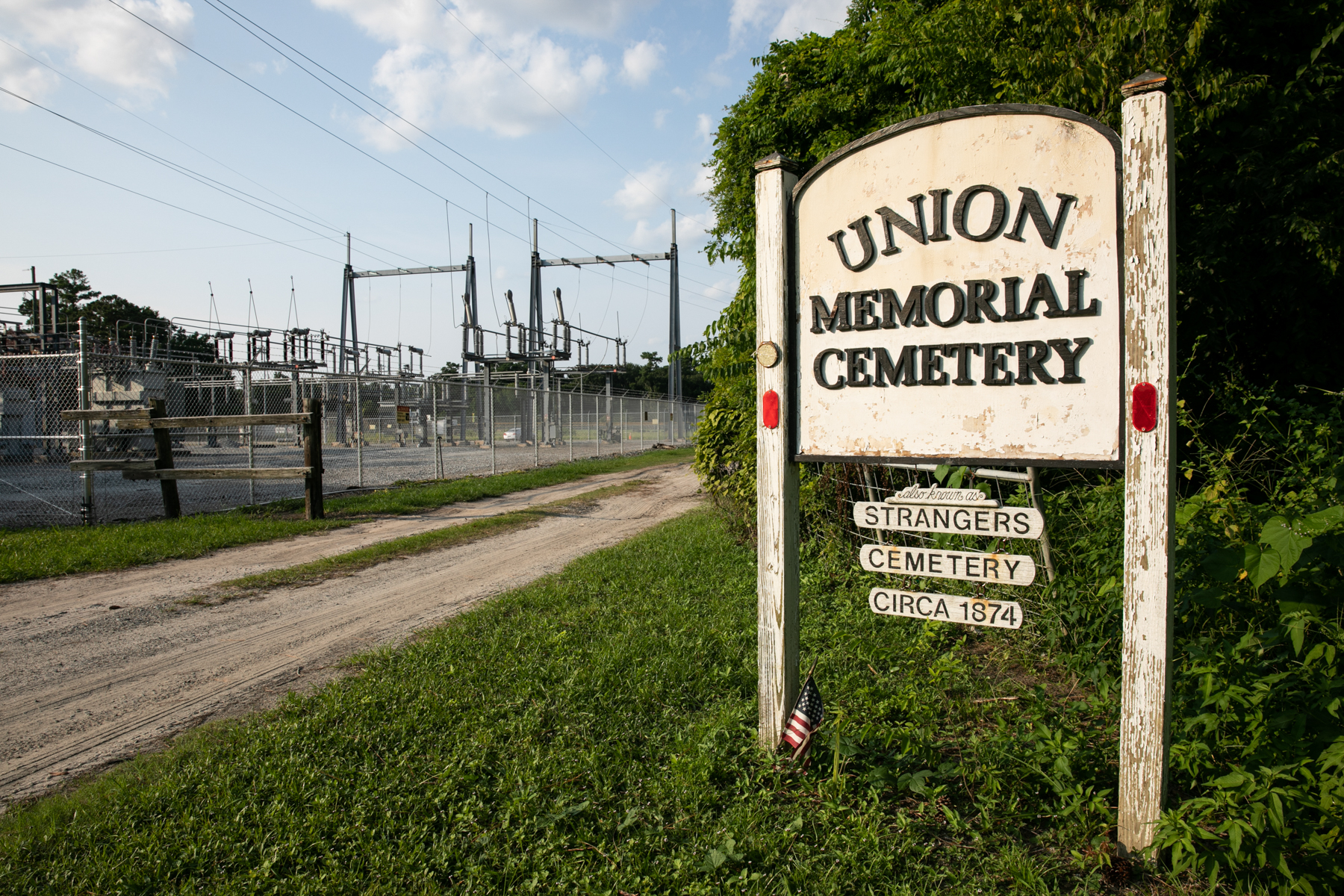

This year, students interviewed relatives of people buried at Strangers Cemetery. Originally called Union Memorial Cemetery, it became known as Strangers because it was the burial ground for African Americans who could not trace their ancestry back to the former plantations.

Roberts, 74, has relatives buried at both Retreat and Strangers cemeteries. Her mother, father and two sisters are buried at Retreat, while her brother and uncle are interred at Strangers.

Even though her brother could have been buried at Retreat, “he didn’t like the idea of golf balls hitting him in the head,” she said.

Her late husband, who was from Liberty County, also is buried at Strangers.

Roberts has been unendingly generous with her time, Dr. Pavich said, helping identify people for her students to interview and showing her classes around the island.

Lessons learned

Student Denise Fraser, who is majoring in liberal studies, interviewed two sisters, ages 90 and 96, whose parents and a few other relatives were buried at Strangers Cemetery.

Fraser, who is from Boston, said the class opened her eyes to the history of African Americans in Coastal Georgia.

“I just learned about their community and their history of how they came over on the slave ships and some of the traditions that they have passed down, like basket weaving, and just what a really difficult time that they had when they came here,” she said.

Mercer alumnus Ashton Walker, who graduated in 2017, recalled his interview with a musician on St. Simons.

“It was really interesting to see the sort of religious and musical language that he used to process his own personal history, his cultural history and the matrix of things that make up Southern history,” Walker said.

Even after he graduated, Walker continued to bring his wife and children to St. Simons to hear the students’ annual program.

“History is always contested. It’s always fraught,” he said. “For that community, I think (the project) is a really important focal point that (provides a space for) things that aren’t always told and always preserved the way others are maintained.”

Today, he lives in Clarkston, where he sits on the city’s Historic Preservation Commission. He would like to replicate the oral history project there, he said.

Mercer alumna Tammy Wages graduated in 2018, but she enjoyed the project so much that she still works on it as a mentor to current students.

“We are giving a voice to the African American community on the island,” she said. “By bringing their voices to light and recording their history and their stories, this is something that will stay in the historical society and the community indefinitely.”

She said she feels the project makes a difference in the community, and “if we can make a change, that’s something I want to be a part of.”