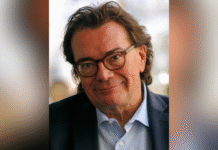

If you’ve enjoyed the past decade of Mercer football, you have in large part Walter Homer Drake Jr. to thank.

William D. Underwood had been president of Mercer University for only three years when Drake, an alumnus and influential U.S. bankruptcy judge, became chair of the Board of Trustees in 2009.

“And that’s when the great conspiracy began,” Underwood recalled. He smiled at the memory. “He thought we should play football, and I had become persuaded by some of our alums and friends that if we did it right, it would make sense.”

That set off nearly two years of listening sessions and planning, and in 2010, the Board of Trustees took up the issue. Judge Drake thought the vote to restart intercollegiate football would be unanimous. Underwood wasn’t so sure. They bet a steak dinner on it.

“It came time for the vote, so Judge Drake called the question,” Underwood recalled. “And he said, ‘All in favor say, ‘aye.’” People said ‘aye’ around the room. He said, ‘It’s unanimous.’ And then he turned to me, and he said, ‘You owe me a steak dinner.’”

Underwood laughed. “He never gave anybody a chance to vote ‘no.’”

With approval to resume football secured, Judge Drake and his wife, Ruth Drake, gave the lead gift to help construct the new stadium, and the field house was named in their honor.

In 2013, the Bears played their first football game in 72 years.

Judge Drake, now a Life Trustee, is pleased with the results of restarting the program.

“The return of football to the University was the major catalyst in reviving interest in the University among its alumni, leading, I think, directly to the improvement of many of the areas of the University,” he said recently from his home in Newnan.

Judge Drake’s legacy doesn’t end — or begin — with football.

A Double Bear who earned his undergraduate degree in 1954 and law degree in 1956, Judge Drake became a prominent figure in bankruptcy law and was influential in the passage of the Bankruptcy Reform Act of 1978, which revolutionized the field.

For over half a century, he served as a U.S. bankruptcy judge for the Northern District of Georgia, retiring in 2021. In addition, he founded the Southeastern Bankruptcy Law Institute, which is dedicated to continuing the legal education of attorneys in bankruptcy law.

Judge Drake is a fervent supporter of Mercer Law School, which established an endowed chair in bankruptcy law in his honor. Beyond the Law School, Judge Drake also supports the University’s Southern Studies program and Mercer On Mission, among other initiatives.

“Everything I’ve ever asked Judge Drake to do to help the University, he has jumped in with both feet and done,” Underwood said. “I can’t imagine a more loyal or committed supporter of our work than Judge Drake.”

A pioneer in bankruptcy reform

Judge Drake was born in Colquitt in 1932 and moved to Newnan when he was 8 years old. He graduated as valedictorian from Newnan High School in 1950. A Georgia football fan, Judge Drake initially enrolled at the University of Georgia but soon transferred to Mercer.

“The big university didn’t suit me at the time,” he said. “I liked the smaller school better.”

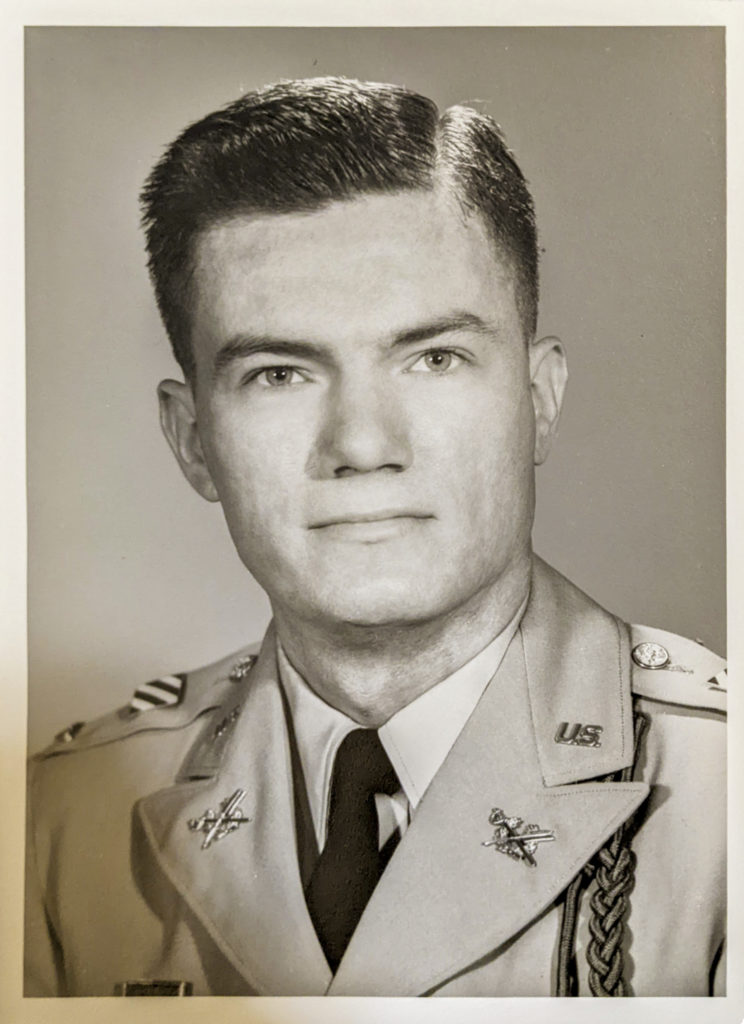

He initially planned to study to be a doctor but started hanging out with pre-law students and decided to pursue law instead. He was active in the ROTC program at Mercer and upon graduation served in the U.S. Army Judge Advocate General’s (JAG) Corps.

Three years later, Judge Drake left the JAG Corps to work at a law firm in Atlanta, writing charters and leases for corporate clients. The work didn’t appeal to him, though, and he left to open a law practice in Macon.

In 1961, he became law clerk to U.S. District Judge Lewis R. Morgan, who in 1964 appointed Judge Drake as a U.S. bankruptcy judge in the Northern District of Georgia. The position was called a bankruptcy referee at the time and fell under the district courts.

“At that time, the bankruptcy laws were totally inadequate to be the tribunal in which major commercial and individual debtor-creditor matters were decided,” said Judge Drake, who as a new referee was surprised at the informality of the bankruptcy proceedings. Referees didn’t wear a judge’s robe and did not have assigned courtrooms to meet in.

In a symbolic move, Judge Drake began wearing a robe and secured courtroom space for his proceedings. At the same time, he started working with other referees to improve not only the status of the bankruptcy courts but also the bankruptcy system.

“There were several of us who decided to do what we could to make the bankruptcy court a separate court within the federal court system and for the next several years worked diligently toward that end in cooperation with leading commercial insolvency lawyers throughout the country,” he said.

His leadership, which included testifying in front of a congressional bankruptcy commission and lobbying Congress, led to the passage of the Bankruptcy Reform Act of 1978, which was signed by then-President Jimmy Carter, whose attorney general was Judge Drake’s friend and Mercer Law alumnus, the late Griffin B. Bell. Carter is now a Mercer Life Trustee.

“The Bankruptcy Reform Act really is the most important bankruptcy law enacted. It really modernized the whole bankruptcy system,” said Mercer Law professor Mike Sabbath, who held the Southeastern Bankruptcy Law Institute/W. Homer Drake Jr. Endowed Chair in Bankruptcy Law.

Not only did the act bring more respectability and dignity to the bankruptcy courts, but it improved the system for the debtors and creditors who had to go through it.

“The improvement was important to the United States, because bankruptcy is an important part of our legal system and at the extent you upgrade it, it benefits our society to have a modern, up-to-date bankruptcy system with lawyers who are well trained,” Sabbath said.

A kind man

Amid his work reforming the bankruptcy system, in 1969 Judge Drake married Ruth Bridges, who earned her bachelor’s degree in education from Mercer in 1959. Although they had met at Mercer, they didn’t really get to know each other until Judge Drake’s dad, who was superintendent of Coweta County schools, offered Ruth a job in Newnan.

They had two sons, Walter Homer Drake III and Taylor Bridges Drake, who also graduated from Mercer Law, and six grandchildren. Grandson Harrison Drake plays on the men’s basketball team at Mercer. Ruth Drake died in 2015.

Despite his standing as a decorated bankruptcy judge who has won numerous service and leadership awards, Judge Drake remains humble, said Sabbath, who studied under him when he served as an adjunct law professor at Emory University.

“He goes out of his way to make those around him feel good,” Sabbath said. “And he never uses his stature in bankruptcy law to belittle, to make anybody feel less. He just has that way about him.”

And although he had “no patience for fools,” if lawyers were prepared when they walked in his courtroom, he was a gentleman, he said. Judge Drake “treated everybody respectfully, and lawyers just loved appearing in front of him,” Sabbath said. “He might not always rule in their favor, but he treated people with dignity.”

Sabbath recalled a time when he was attending a Mercer football game with Judge Drake. The pair was headed to the president’s box in the Homer and Ruth Drake Field House when they were stopped by a new security guard.

“Excuse me. Where are your passes?,” Sabbath recalled her saying.

“Well, this is Judge Drake,” Sabbath replied.

The woman stood firm.

“I don’t really care who he is; you need to have a pass,” she told him.

When Sabbath explained this was the Drake for whom the field house was named, the woman became embarrassed.

But then “the judge put his hand on her shoulder and said, ‘Young lady, you’re doing your job. You did exactly what you’re supposed to do.’ And he complimented her for the work she was doing,” Sabbath recalled.

“Judge Drake actually made her feel good about herself, and I’m thinking, ‘What a nice man.’”