Mercer faculty members just wrapped up a whirlwind spring semester that was anything but normal. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, they had one week in March to transition all their courses to an online format, with some requiring some major outside-the-box thinking.

Logistical challenges

Dr. Katie Northcutt, associate professor of biology and director of the neuroscience program, had minimal online components for her neurobiology, comparative animal physiology, and anatomy and physiology courses at the start of the semester. She said it was a stressful week of logistical challenges, but she learned a lot about the virtual tools that are available and how they can be incorporated.

“My strategy throughout this whole change has been to keep things as similar and consistent as before, because students had spent nine weeks getting used to the way I was doing things,” Dr. Northcutt said.

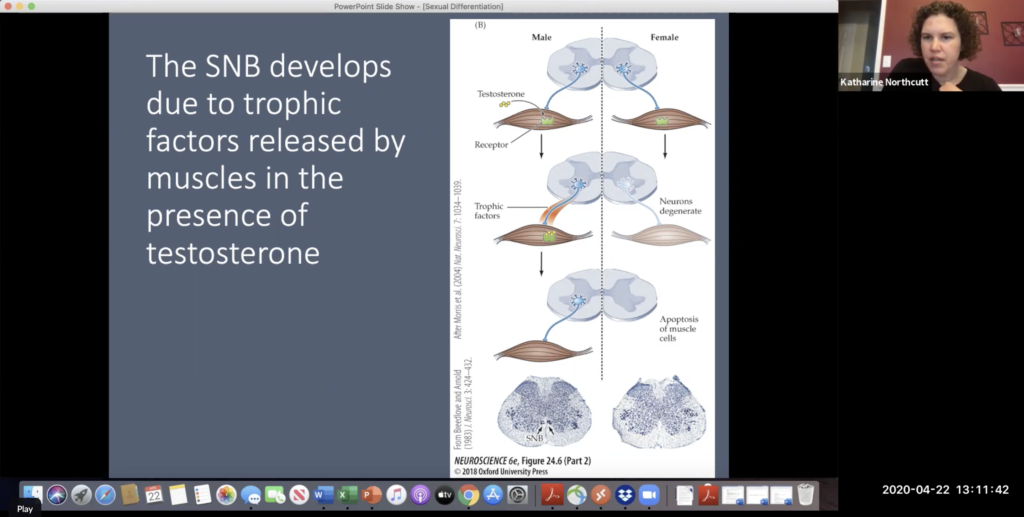

Her students wanted to meet together on Zoom during their regularly scheduled lecture class times. Northcutt shared her computer screen and went through PowerPoint slides, which students could access beforehand, so they could follow along with her. She also shared video of the presentations, so students who couldn’t meet at the scheduled time could watch on their own.

The biggest challenge for Dr. Northcutt was adapting the labs for her courses. She had to figure out ways for her students to learn the material while not being able to perform the typical lab activities. Since her anatomy and physiology students couldn’t do the cat dissection, she walked them through it using photos and diagrams she prepared in the fall and quizzed them on identifying structures.

For comparative animal physiology, she ran simulations for her students and gave them data to analyze and interpret. For instance, they did a case study on movement disorders and used patient symptoms to determine the disorder.

“I think they got everything out of it that I was hoping they would get if we did it in class,” Dr. Northcutt said.

Interactive practice

In anticipation of stay-at-home orders, College of Pharmacy faculty Dr. Lydia Newson and Dr. Kathryn Momary started coming up with a plan early for the Comprehensive Patient-Centered Care course.

This course — a requirement for third-year pharmacy students before they begin their fourth-year rotations — gives students experience interacting with patients and applying the content they have learned, said Dr. Momary, associate professor and vice chair for research in the Department of Pharmacy Practice. A total of 132 students took the class in the spring.

Students often struggle with patient interviews, so it was important for them to have ample opportunities to practice those skills. Dr. Newson and Dr. Momary arranged for post-graduate pharmacy residents to act as standardized patients, and the students did Zoom counseling sessions with them. Faculty members observed the sessions and provided feedback on the students’ performance.

Via Zoom, students also did team-based learning activities where they answered questions and conducted mock interviews of patients or healthcare providers together as a class.

“It’s not the same as being face to face, but the fact is that our new normal is going to require more telemedicine, so the practice is relevant in their future careers,” Dr. Momary said. “We worked hard to execute it. It’s a hard time for many reasons. The students have really risen to the challenge. I’ve been so impressed.”

The art of instruction

Craig Coleman, professor and chair in the Department of Art, switched from in-person class demonstrations to online how-to videos. For his digital imaging course, he made a video showing students how to use software for an animation project, which he said took more time than a live demo but allowed students to refer back to the instructions. Mercer Information Technology worked with the students to give them access to the software.

Students created rotoscope animations, in which the artist draws over individual frames in a video file, depicting gestures that have become part of their daily routine amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Coleman combined the clips and recently projected them on the outside of the art building at night.

“I was really proud of them,” he said. “I thought they did a great job. It’s always fun to see student work projected like that.”

Coleman said the feedback portion of art instruction was more difficult in the online class format. When students were in a room with him, they could ask him questions and receive guidance right away on their artwork. It was harder to know what the students were doing and required much more explanation when the projects weren’t in front of him.

Students in Coleman’s junior/senior studio courses were working independently on self-directed projects and meeting weekly to critique their work, so Coleman moved the conversation to an online discussion board, which offered an advantage because students then had a written record of the comments.

He turned the lectures for his visual literacy class into videos and PowerPoint presentations. Those students worked on online journals, a discussion board for their readings, and final projects or essays, which they discussed with Coleman during Zoom conferences, he said.

Community and engagement

Law professor Karen Sneddon wanted to make sure students in her legal writing and wills, trusts and estates courses experienced the same sense of community and engagement through the virtual format. She held classes online at their regularly scheduled times and helped keep students focused by clearly spelling out what would be covered each day; giving short automatically-graded quizzes to gauge understanding; and providing closing prompts about why the material mattered and what students needed to do before the next class.

“It’s important to have a structure. It’s important for students to feel engaged,” she said. “It’s such unprecedented times. Being able to have the online support has made this as seamless and pain-free as possible.”

Dr. Jeff Hall, professor and associate dean at the Tift College of Education, said it was a relatively easy transition to bring the assessment course he teaches for the Master of Arts in Teaching program fully online, since students already met online half of the time. The biggest change was that students had to give project presentations on Zoom rather than in person.

Dr. Hall and Dr. Northcut both used the breakout room function on Zoom to divide students up for group work. This feature allowed the professors to pop into groups as needed to answer questions and offer guidance.

“I was a bit worried about how that would work, but it actually worked fairly well,” Dr. Northcutt said. “I think students enjoyed being able to work with others in that way.”

A big adjustment

“When students are in front of you, you get a sense of how they’re doing emotionally, professionally and personally,” Dr. Momary said. “When I can’t see them in person, I don’t get that same feedback, and I really miss it.”

Dr. Northcutt said being able to see the students’ faces was helpful in gauging their understanding. If she noticed a student looked stressed, she checked in with him or her later.

“I miss my interactions with them. I still get some of that on Zoom, but it’s not quite the same,” she said. “Constantly being aware of what everyone is dealing with and trying to make sure I am being accommodating, while trying to run the class … that’s been a lot to juggle at one time.”

Sneddon discovered that she actually had better attendance and more classroom participation through the virtual format. Some students were more willing to speak up through Zoom than they were in person. Students also talked to Sneddon individually through virtual office hours.

The online format has presented challenges for some students, like connectivity issues for those in rural areas and scheduling conflicts for those with families. But Sneddon said she was impressed with how dedicated students were to their assignments despite the circumstances. The student projects she received for her wills class were some of the best work she’s seen.

Some students had to drive long distances to get to campus, so the virtual format eliminated one potential stressor in their lives, Dr. Hall said.

“I think the hardest thing for students is just finding the time to do things,” Dr. Hall said. “Many of them have children. Many of them have challenges dealing with work furloughs and getting laid off. Some of my students have lost family members to coronavirus.”