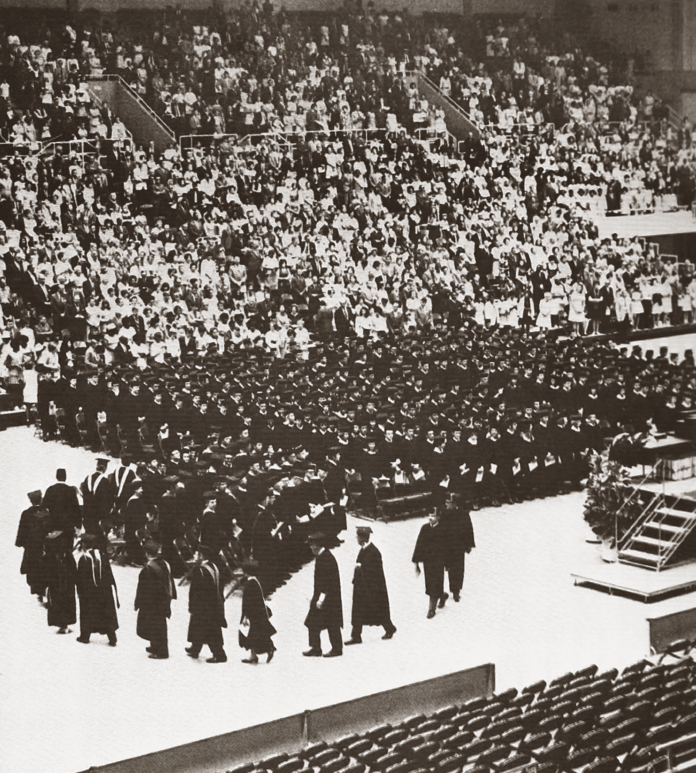

It was a time of growth, not just for students as they prepared for their future but for Mercer University itself. In the four years leading up to commencement, the Class of 1970 witnessed history and change across the nation and world and, spurred by their voices and actions, the Macon campus.

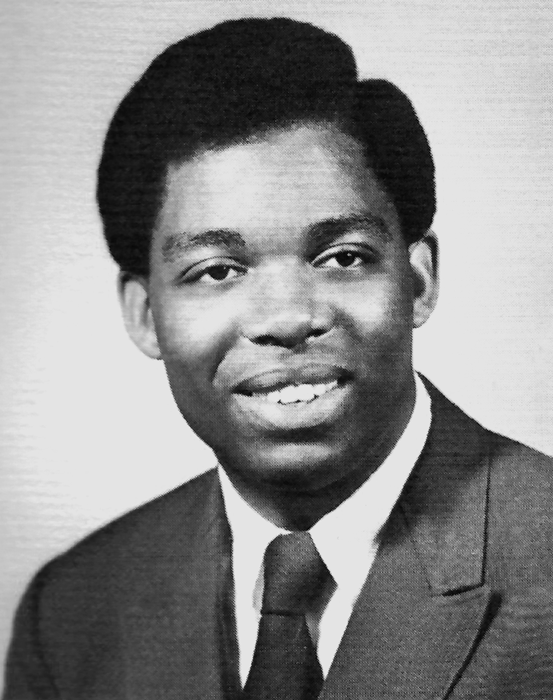

“The Mercer we entered was not the same Mercer that we graduated from four years later. A lot of things changed very rapidly by virtue of having had that push that the school had to integrate the student body,” said Dr. Joseph Hobbs, a member of the Class of 1970 who just retired after a 45-year medical career at the Medical College of Georgia.

“The way I look at those early years, those were the building blocks to create a university experience that not only said it was inclusive but actually lived out that aspect. In doing that, you had to imagine there were bumps along the way. I think it’s a testament to what can happen when change needs to occur, when you have committed people who are not only going to advocate for change but shepherd for change.”

Fifty years later, members of the Class of 1970 shared their stories of what it was like to be a Mercer student during that time and what it means to still be a Mercerian today.

The beginning of integration

In 1963, Sam Oni, Bennie Stephens and Cecil Dewberry became the first Black students to attend Mercer, making it one of the first private institutions in the Deep South to integrate. But an uphill battle toward equality remained, and those early years weren’t easy for students on campus.

“(Mercer) was convinced that the only way this would get better is if there were more black students,” said Dr. Doug Thompson, professor and director of Mercer’s Spencer B. King Jr. Center for Southern Studies.

The Class of 1970 stepped onto the Macon campus in 1966, right as Oni was being denied entry into Tattnall Square Baptist Church.

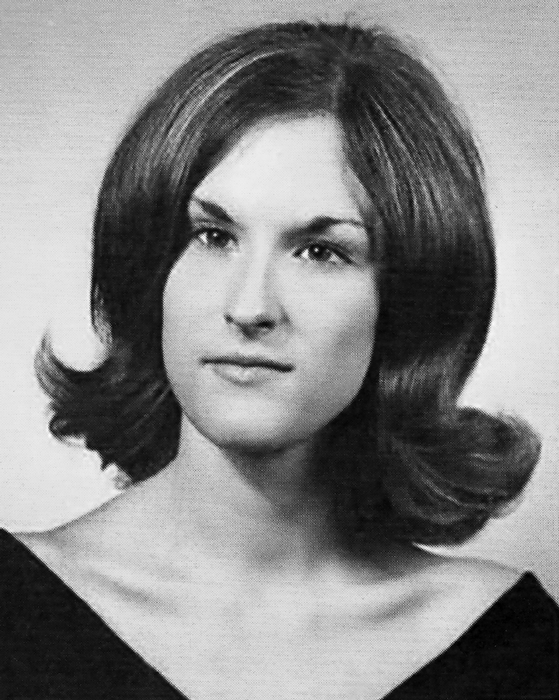

“I remember that day, and I remember being totally shocked that somebody couldn’t go into a church,” said Sandra (Orr) Sizemore, a 1970 graduate and retired teacher. “I grew up in the North, and this was a culture shock.”

About 20 Black students were in Mercer’s freshman class in 1966, many recruited through the Upward Bound program and by beloved faculty member Dr. Joseph “Papa Joe” Hendricks.

By their senior year, the atmosphere around the country might best be described as “social chaos,” Dr. Thompson said. The nation had become comfortable with the process of desegregation, but racial equality and representation were far from realized.

“Back in 1966 when we started, race was a big issue,” said Isabelle (Smith) Tanner, a member of the Class of 1970 who went on to careers with General Electric and State Farm. “How Mercer changed me the most was just the diversity that was not available where I grew up. It broadened my world. All of that has influenced my thinking and my life since then.”

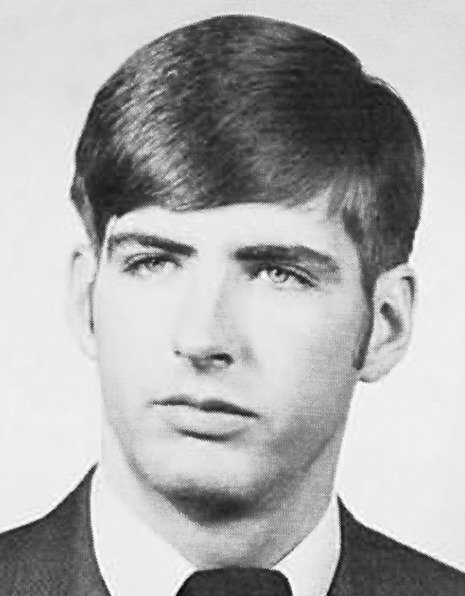

In addition, the war in Vietnam was escalating as the Class of ’70 got closer to graduation. Lamar Sizemore, who went on to graduate from Mercer Law School in 1973 and have a 46-year law career, remembers being in his fraternity house as draft numbers were called. He already had signed up to go into the military after graduation.

“We married right after college,” said his wife, Sandra Sizemore. “In a couple years, he was going to Vietnam, and that affected everything. It was a big black cloud that loomed over us.”

Fighting for what’s right

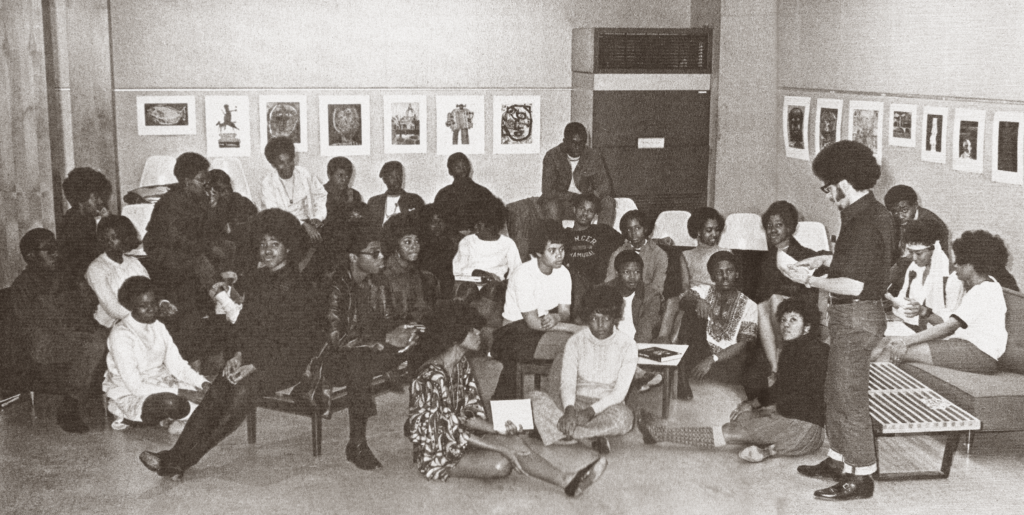

College students across the nation stepped in to fight for what they believed in, participating in sit-ins, marches and protests, Dr. Thompson said. On Mercer’s campus, members of the Black Student Alliance, created in 1969, protested their omission from the 1969 yearbook by burning several copies of it, according to Mercer archives.

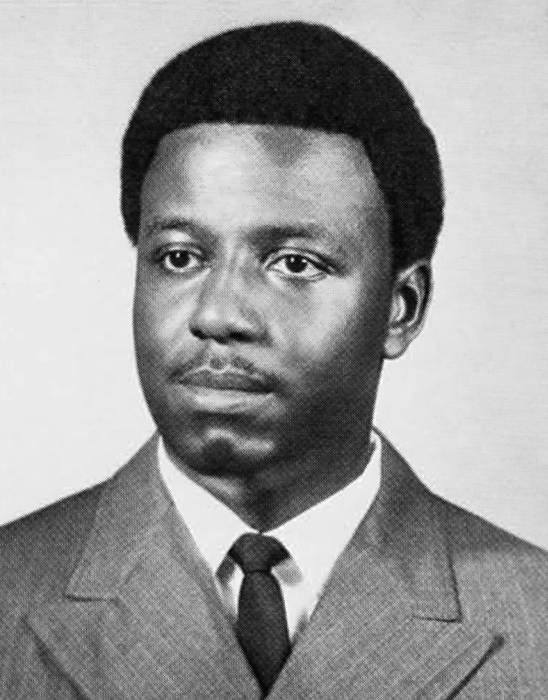

James Norman, a 1970 graduate who spent 25 years as president and CEO of Action for a Better Community and served the community in a number of other roles, said the campus organization also petitioned to bring speakers like civil rights activist Dick Gregory and “Roots” author Alex Haley to campus, and protests were held to call for the hiring of faculty members of color.

Black students also held a peaceful protest at the co-op (now the Connell Student Center) to call for the addition of a Black studies curriculum, Dr. Thompson said.

“By 1969-70, Mercer has turned a corner on the number of Black students here, so they become a visible presence on campus. They can start demanding things that are important,” he said. “It’s an important story to tell, that those students realized they had not gained all of the benefits of desegregation at Mercer.”

They wanted greater representation, including in the curriculum, and their sit-in worked. Mercer faculty approved a Black studies program in a 52-36 vote in February 1970, and it started in 1971, said Dr. Mike Cass, a Mercer faculty member from 1969-2008.

“The African experience in the United States is crucial to what these nations, including the United States, turned out to be,” said Cass, who taught the first four literature courses in the Black studies program. “It was ignored everywhere except historically Black colleges. If you believe in integration, you better start teaching the whole of American history the best that you can. It’s not both sides. It’s one side. It is American history.”

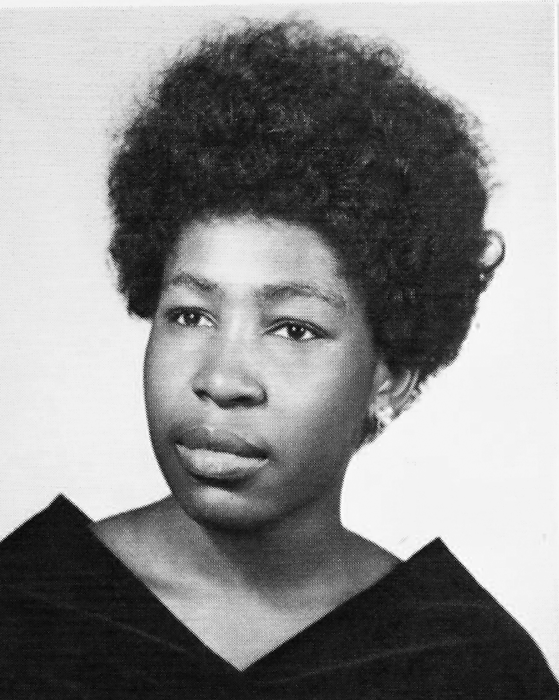

Alice (Burns) Boykin, a 1970 graduate, recalls her time at Mercer being comfortable, although there were still problems and things Black students weren’t allowed to be a part of, such as Greek life.

“Did we experience racism? Yes, but not very overtly. We were (some of) the first Black students on campus in the dorm,” said Boykin, who spent the majority of her career working with the state Social Security disability program. “Hopefully, we laid a groundwork that others could build on. It was mostly a good experience.”

Norman said Mercer’s diversity today is a source of pride for him. He called Mercer a role model that’s ahead of state institutions. Black students account for 28% of undergraduates at Mercer — mirroring the population of the state of Georgia — compared to 8% at Emory University and the University of Georgia, and 7% at Georgia Tech. The percentage of Black undergraduate students enrolled at Mercer also is three to four times that of private schools considered peer institutions.

“Slowly but surely, we were able to demonstrate that we were just like everybody else, so the expectations should be no different. That process occurred by the work of these Black students,” said Dr. Hobbs.

Finding a support system

The Class of 1970 found support and encouragement through friends and faculty members.

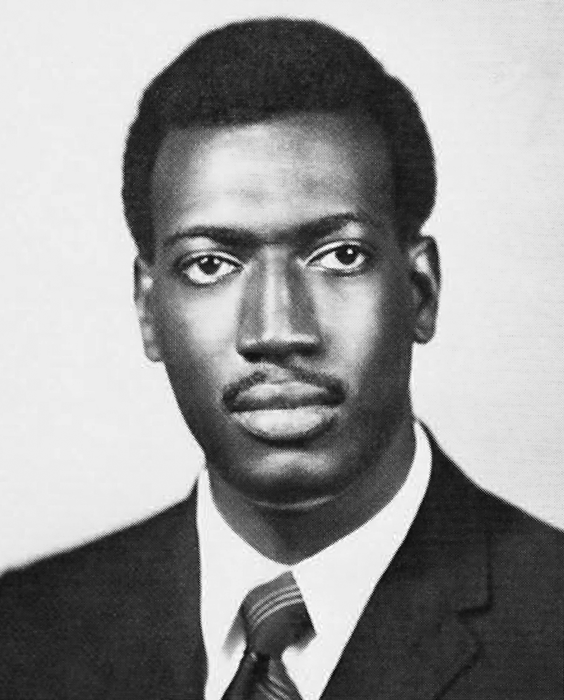

Renata (Williams) Boston, a 1970 graduate who joined her family’s mortuary business, said she, Norman and Dr. Hobbs were among several Black students who came to Mercer from Augusta and knew each other from high school. She said those relationships helped her to adjust to the integrated environment and her first time away from home.

“Those people from Augusta made me feel comfortable that even if this was difficult, I would have some people to lean on,” Dr. Hobbs said. “We got there, and I truly believe there was an effort to create an inclusive community.”

Dr. Hobbs recalled Dr. Hendricks visiting his high school in Augusta to talk with some of the seniors. He had decided to go to Howard University in Washington, D.C., a historically Black college, but his classmate Carl Brown convinced him to visit the Mercer campus, where he met Dr. Hendricks again, and everything fell into place. Brown and Dr. Hobbs became roommates for all four years at Mercer.

“It was something about the personality of Dean Hendricks that made me believe as a student that if I worked hard, he would make sure that that other stuff was taken care of,” Dr. Hobbs said. “That was a little naive, to think that one person could do that, but I think that he sold us (on Mercer) … that they were doing this because they believed it was the right thing at the time.”

In addition, he formed relationships with the other freshman students in the dorm, creating a “bridge across the anxiety,” he said. James Boykin, a 1970 graduate who served the Army for 14 years and was a law enforcement officer for 26, said he made friendships that have lasted for 50 years.

Dr. Hobbs said faculty members reached out individually and were interested in his academic success and helping him through the challenges. Dr. Joseph Hendricks and professors Dr. Jean Hendricks and Dr. Tom Trimble were a few of the faculty that the alumni said were instrumental in making their time at Mercer comfortable.

“Coming to Mercer was like a whole new world. Part of the experience was adjusting to that reality and negotiating that environment,” Norman said. “What I found was that there were some people at the University who were very dedicated to changing the face of the University and understood that was going to be a challenge for the students as well as the school itself.”

Dr. Joseph Hendricks and his wife, Betty, invited the Black students often to their home to check on them. Dr. Hendricks knew each of the students personally and how they were doing academically, and he was always there to help, Boston said.

“Dr. Joe Hendricks, he was an inspiration,” Alice Boykin said. “If you can imagine, back in 1966, I think all of the Black students in our class came from predominantly Black high schools. It was our first experience in an integrated situation. Dr. Hendricks made us so comfortable. He was a mentor; he was a father figure. If you felt down during the week, you could go talk to him. He always made himself available.”

Students also made connections with the Macon community, sometimes in the most unlikely of places. Norman and his friends went to the Krystal fast food restaurant in downtown Macon late at night at least once a week to study. A woman who worked there became a mother figure to them and always made sure they ate well. She attended their graduation and surprised them with cufflinks as a gift, he said.

Challenging gender bias

While modern elements crept into life in other ways, old attitudes about women remained on the Mercer campus in the late ’60s, Sandra Sizemore said. Women could only wear shorts to gym class or to the post office on Saturdays, and even then, they had to wear raincoats over them.

Blanche (Smith) Presley, a retired teacher who still instructs with the eCore program, said women could only wear pants if they were part of a pantsuit. This was quite new to her and twin sister Tanner, as they’d never owned or worn pantsuits growing up. Shortly after, the rule was changed, so pants could be worn on Saturdays.

Female students had to be in their dorm rooms at 10:30 p.m. Sunday-Friday and 11:30 p.m. Saturday, while male students had no curfew, Sizemore said. In the spring of 1969, the outdated rule was suspended after students gathered on the quad one evening in protest of the curfew.

“The status of the female student changed dramatically,” said Presley, who became Mercer’s first female class president.

In addition, Mercer female students could only live in dorms and not apartments. Presley said she and Tanner caused a bit of a stir when they rented an apartment for their senior year at Mercer. The previous two summers, they had lived in an apartment in Atlanta while student teaching. Once back in Macon, they didn’t want to go back to dorm living. Since they would be student teaching in the community and wouldn’t be on campus much anyway, they rented an apartment on New Street.

A few weeks into the semester, they were invited to tea with President Rufus Harris. He talked to them about their plans and experiences, they got the OK to stay in their apartment, and the rule was changed shortly after.

New and old traditions

Some Mercer traditions still observed today were going strong more than 50 years ago, like participating in intramural sports, signing your name at the top of the Administration Building and seeing the University’s roots in Penfield.

Class of 1970 members remembered some traditions that no longer exist at Mercer, like attending mandatory chapel services twice a week.

“Even though it was something we were required to do, I rather enjoyed it because of the inspirational messages. It shaped my experience at Mercer, and it has made a difference in the work I have done and still do,” Norman said.

Playing bridge at the co-op was big for the Class of 1970, as was watching basketball games in Porter Gym.

“It was wall-to-wall people,” Lamar Sizemore said. “That little building just felt like it was rocking back and forth with the cheering that was going on.”

Some talented musicians came to Mercer for Homecoming, and students really enjoyed the concerts, James Boykin said. Soul legend Otis Redding had been booked to perform for Homecoming but died in 1967 before the concert. Presley recalled the devastation felt across the campus and community after his death.

The “Cluster” student newspaper was spreading news to the Mercer campus back then too. Class of 1970 member Gary Johnson became the first Black editor his senior year, and James Boykin and Dr. Hobbs were also on the staff. Dr. Hobbs said it was a politically charged editorial staff, and he wrote antiwar pieces about Vietnam.

Finding love at Mercer wasn’t uncommon during those days either. The Sizemores, of Macon, and the Boykins, of Springfield, Illinois, are two couples who met their freshman year in 1966 and graduated and married in 1970, bringing extra significance to their 50th anniversary this year.

See “then and now” photos of Class of 1970 members and hear how Mercer shaped them.

Note: Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the University decided to forego the traditional 50th Class Reunion and Half Century Club Brunch this year. The Office of Alumni Services will work with those groups on plans for rescheduling in the future. Details will be posted at homecoming.mercer.edu as they become available.