A Mercer University professor hopes to bring physics lessons to more high school students and teachers in Middle Georgia with a new, low-cost curriculum.

Dr. John Lee wanted to do this project for many years, and his interest grew even stronger when he taught a two-week physics camp for the Bibb County School District in summer 2014. With funding from the University’s “Research That Reaches Out” Quality Enhancement Plan (QEP) this past summer, he and Mercer seniors Zainil Charania and Savannah Grunhard were able to create a curriculum containing 10 activities.

A 2016 report by the Education Week Research Center found that two in five high schools across the country don’t offer physics classes. Four of Bibb County’s six high schools provide physics or advanced physics, said Brian Butler, school improvement coordinator of science for the district.

“This is the least taught and least interested subject for high school students,” Dr. Lee said. “Nationally, less than 40 percent of all students take at least one physics course in high school.”

That compares to about 100 percent for biology and 70-80 percent for chemistry. Considering how science courses are taught, physics may be perceived as the most unrelatable subject because it generally focuses more on equations and less on hands-on activities, Dr. Lee said.

However, students pursing science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) majors in college may find themselves unprepared for higher-level physics courses if they miss the basics in high school, said Glenn Harman, physics teacher at Central High School and Mercer adjunct physics professor. Grunhard, a finance major and chemistry and biology minor at Mercer, said that was the case for her.

She didn’t take physics in high school and struggled at first in college without that science background. She wanted to get involved in this curriculum project so she could help high-schoolers start their college experience with a stronger understanding of physics.

“It can be a challenging subject because oftentimes it’s very lab intensive and math intensive,” Butler said. “Sometimes students are scared of it and apprehensive to take the course.”

Physics labs require the use of sensors that are expensive. When schools have limited budgets to cover all of their science subjects, that physics equipment is usually the first to get cut, Dr. Lee said. Plus, it doesn’t make sense to buy pricey materials for a small class, Harman said.

Dr. Lee said his curriculum, however, uses smartphones along with the apps Physics Toolbox Suite and PhyPhox instead of expensive sensors. Using phones makes the subject more approachable for students, Butler said.

Smartphones have sensors that can measure things like motion, proximity, magnetic field and pressure variation, and data can be measured and analyzed through the apps, Dr. Lee said. In addition, the phone’s microphone and speakers can be used for sound wave experiments.

The curriculum includes assembly instructions for some simple apparatus, all of which costs $30 or less to build; materials lists; step-by-step instructions for eight student lab activities and two demonstrations; and teacher manuals. Harman provided guidance so the lessons would meet state education standards.

All the lessons are very interactive and allow students to “see physics in their everyday life,” Grunhard said.

“I’m just really excited for this project. It’s not only helpful to the school but it’s helpful to the teachers because it gives them the ideas for the labs and they can just execute it from the curriculum.”

Many high school physics teachers don’t have degrees in physics, Dr. Lee said. This easy-to-use curriculum costs teachers nothing and minimizes the time they have to invest in creating lesson plans.

Dr. Lee hopes to pique the interest of teachers who are not physics-certified and help them gain more solid physics knowledge so they can better implement their lessons. He wants to hold some professional development workshops to train teachers in the physics curriculum in the future.

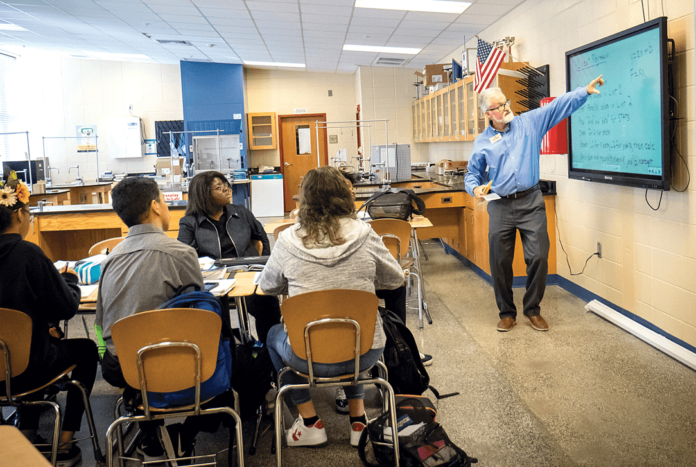

Central High School is piloting the curriculum right now, and the plan is to roll it out to the remaining Bibb high schools this spring and during the 2019-20 school year, Butler said.

“The goal is to bring it as far as possible,” Dr. Lee said. “That’s why we start with Bibb County, and we’ll try to see if we can attract interest from other surrounding counties.”

One of the demonstrations in the curriculum explains the “beat phenomenon” by having two phones play monotones of slightly different frequencies. One of the labs uses a free video analysis computer software to study the projectile motion of a ball rolling down a track.

Harman said he has done the curriculum’s spring/mass experiment with his junior and senior International Baccalaureate (IB) classes and sophomores in Physics 1. Students determined the strength of springs by hanging different masses from them and calculating how much they stretched. They also attached their phones – and additional weight – to springs and used apps to measure the movement or “oscillation.”

The IB students are required to perform 10 hours of individual experiments, and four of his students have been using the same smartphone apps for them.

“Anytime we can increase rigor, that’s always a good thing,” Butler said. “This is adding another tool to help students be engaged and successful.”