This year marks the 40th anniversary of the nation’s first reported cases of the disease that would later become known as AIDS.

Over the past four decades, Mercer University professors have contributed to the research of the disease while providing education to the community and compassionate care for those living with it.

Today, contracting HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, is no longer a death sentence, and with proper treatment, people with HIV can live long, fulfilling lives.

But there’s still much work to be done, especially in Georgia, which has the highest rate of HIV/AIDS in the nation.

So, professors like Dr. Harold Katner, Dr. Jeffrey Stephens and Dr. Bonzo Reddick in the School of Medicine and Dr. Chinekwu Obidoa in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences continue their work in an effort to help end the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Pioneering HIV/AIDS care in Macon

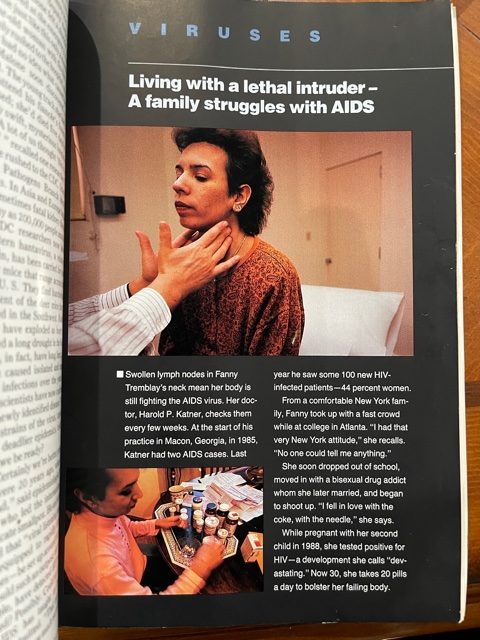

Dr. Katner saw his first patient with HIV on July 1, 1983, in New Orleans. Two years later, he took a job at Mercer and moved to Macon, where he saw some of the first HIV patients in Middle Georgia.

“It was a nightmare because everybody was afraid of it,” said Dr. Katner, professor of internal medicine. People “thought I was bringing all the AIDS patients to Macon.”

In addition to the stigma surrounding the disease, there was no treatment for it until 1987.

“In dealing with a disease that at the time was 100% fatal, I felt really helpless,” Dr. Katner said. “And so, I could manage, maybe, infections, but sooner or later, they’d get something I couldn’t treat, or the infection would overwhelm the patient.”

What he could do, though, was educate young people about HIV/AIDS prevention. Recalling a study that found a connection between seeing a friend die of AIDS and changing a person’s own behavior, he put together an education program that showed the cases that impacted him the most.

“I started going out in the community to raise the awareness,” he said. “I mean, how could a child make an informed decision about a behavior if they don’t know the consequences? Not just a child, but anybody.”

Since then, he has presented over 500 community education programs, which included a long-running program with Houston County schools in which he talked to thousands of young people about sexual health.

Some people criticized Dr. Katner for the graphic images he included in his presentation, which touched on the different stages of the sickness and risk factors, including unprotected sex and drugs. Some patients attended the talks with him, to show that not everyone fit the stereotype of someone who was infected with HIV.

“It was not just gross pictures,” he said. “It was trying to put a human face on my patients through what I experienced with them in their deaths and their progress.”

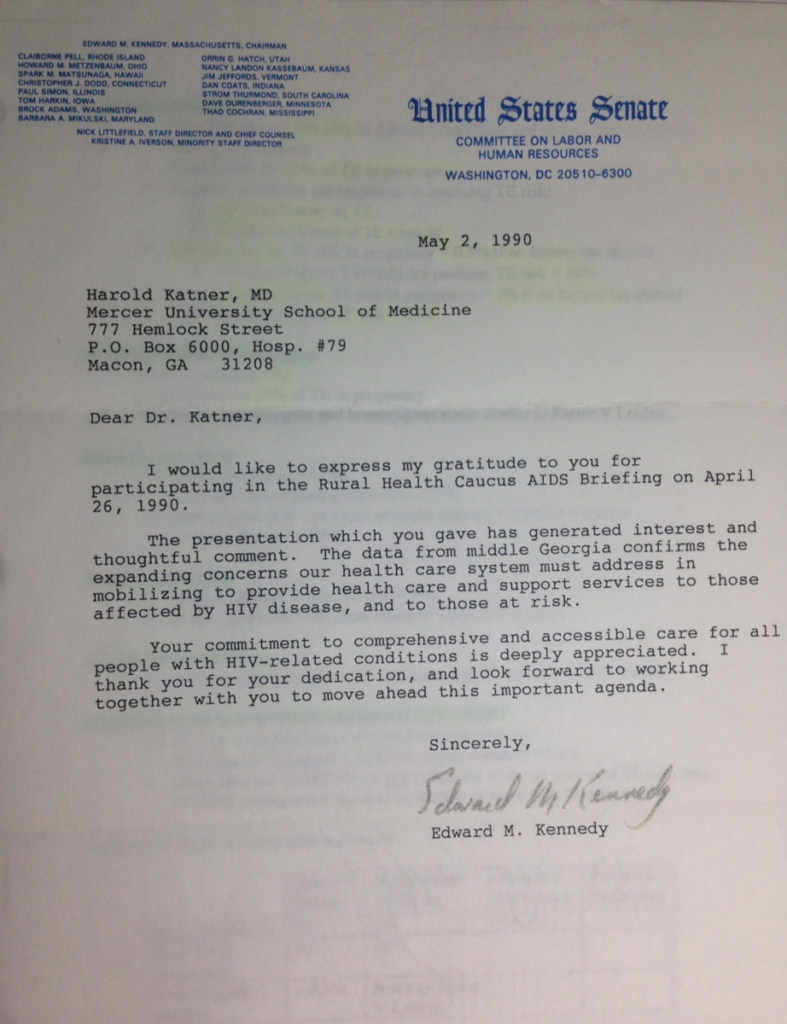

In 1989, Dr. Katner helped found Compass Cares, a public health clinic in Macon that specializes in outpatient HIV/AIDS treatment. It’s funded by grants from the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program, whose creation Dr. Katner advocated for through testimony to a U.S. Senate subcommittee.

Over the years, he’s worked with pharmaceutical companies on a number of drug studies researching medications to manage HIV.

“Some of these drugs really save people’s lives, so they’ve been very, very beneficial,” said Dr. Katner, who also serves as chief of the infectious disease clinic for the Macon-Bibb County Health Department and is on staff full time at Atrium Health Navicent in Macon, where in the early days he set up the hospital’s needle stick protocol.

As a professor at Mercer, Dr. Katner has trained not only students who work in primary care but also many who have gone on to run HIV/AIDS clinics across the state.

To many patients, Dr. Katner was not only their physician but their friend.

He recalled working with a nursing student when she discovered her ex-husband infected her with HIV. She wanted Dr. Katner to promise that he would keep her alive long enough for her to become a nurse and take care of her children.

One week before graduation, she began to experience shortness of breath. She ended up in the hospital and received her diploma at her bedside. Soon, she began to get worse.

“She knew she was dying,” Dr. Katner said. “She asked us to bring her kids to her bedside every day, so she could hold them. … To watch a mother die holding her babies is the most horrible thing I’ve ever seen in my life.”

Researching new drugs

Among Dr. Katner’s students who went on to work with HIV/AIDS was Dr. Stephens, professor and chair of internal medicine.

Dr. Stephens, an infectious disease specialist, saw his first HIV patient in 1985 when he was a third-year medical student at Mercer. During his residency at Emory University, he noticed about a third of his hospital admissions were HIV patients. Then, during a fellowship at Wake Forest University, he became interested in medication for HIV.

At the time, the only HIV/AIDS treatment available was AZT, “which we found out later by itself is really almost no benefit. It’s minimal, minimal benefit,” he said.

He began working on clinical trials for new drugs to treat HIV/AIDS, which resulted in a second drug being approved for HIV.

Dr. Stephens continued his work when he joined the faculty at Mercer in 1992, and for nearly 30 years he has had an active research program of clinical therapeutics, which led to the approval of many more drugs to treat HIV/AIDS.

“We had one drug in 1987, and we have more than 30 now,” he said.

While patients still have to take a combination of drugs for treatment, they take far fewer than was needed at the beginning of the epidemic. There’s even a shot that combines two drugs into an injection that’s given once a month.

Dr. Stephens is studying an injectable drug that could be given once every six months.

“I’m working with a new class of drugs called capsid inhibitors that have the possibility of being given once or twice a year,” he said. “The problem is that you have to have (another drug) that you could do once or twice a year, so we would not be able to use that by itself.

“But the idea would be now with injectables, you don’t have to take a pill every day.”

Many of the drugs used for treating HIV/AIDS also are used as prevention, he said. Currently, only oral medications are available for pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, and Dr. Stephens is examining whether injectables could be used to prevent HIV/AIDS as well.

“We can basically stop HIV between treating it appropriately and folks taking preventative medicine, but very few people actually take them,” he said. “It has been shown at least in trial that people getting injections tend to do better for prevention because obviously when you’re taking a pill, a lot of people miss doses, and by the way, people miss doses when treating it too. …

“That is one of the big problems. These medicines are great, but you have to take them almost perfectly, and we’re not robots. We’re human beings, and there are a lot of reasons why people can’t take their medication.”

Dr. Stephens also sees patients at Compass Cares, and many of the patients there have participated in clinical trials that have led to drug advancements.

“We have many patients that we’ve been following now since the mid to late ’80s and early ’90s, and they’ve grown old with us. And they’ve retired, and they’ve had full lives,” he said. “And that’s the thing that really has been a major change. Now HIV is an easily treated illness. You can live a normal life.”

Educating and empowering youth

Still, the best way to combat HIV/AIDS is prevention, and another Mercer professor has been among the largest providers of HIV/AIDS community education in Macon in recent years.

Dr. Obidoa, associate professor of global health studies and Africana studies, has been involved in HIV/AIDS research for about 18 years. Her research centers on HIV spatial and social epidemiology with a special focus on the sexual risk behaviors of Black youth.

When Dr. Obidoa arrived at Mercer in 2013, there was little research exploring the underlying drivers of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Middle Georgia.

In 2014, she was selected as a Research Education Institute for Diverse Scholars Fellow at Yale University, and in 2015, as part of the program, received a $20,000 pilot grant from the National Institutes of Mental Health to conduct a community-based HIV/AIDS study in Macon.

Her study explored the context of sexual risk taking among Black young adults. This was a groundbreaking study, as virtually no large-scale studies have focused on understanding the drivers of HIV/AIDS in Middle Georgia.

Among the findings was that high-risk sexual behavior is significantly associated with the context in which Black young adults in Macon live, highlighting the need for education and awareness and addressing issues of social injustice that predispose them disproportionately to HIV/AIDS vulnerabilities.

Dr. Obidoa wanted to share the research with the community and in 2017 created and directed the first HIV Summer Institute, which takes place every two years. The institute trains and equips young people with research and skills for community-based HIV/AIDS prevention and intervention, Dr. Obidoa said.

“Young people are very powerful,” she said. “And I think that engaging them in this kind of HIV community-based prevention and education is amazing.”

The first HIV Summer Institute in 2017 delivered a tailored HIV workshop to 134 people in Macon, and the second in 2019 conducted focus groups and prepared a report for Compass Cares. The report was presented to the clinic’s community advisory board to support policy making.

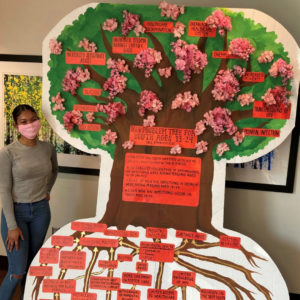

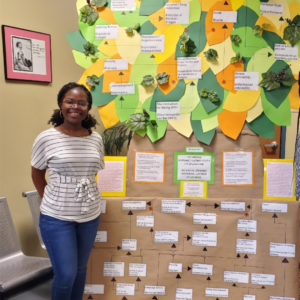

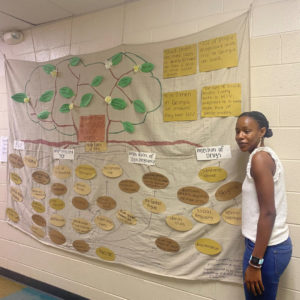

Because of the pandemic, the 2021 summer institute was held virtually. Eight high school students from Macon and the Atlanta area participated in a weeklong immersion program that provided a basic understanding of the pathology and epidemiology of HIV/AIDS and taught them how to analyze the underlying factors driving the epidemic.

At the conclusion of the summer institute, each student created a life-sized HIV problem tree showing the root causes and effects of the HIV/AIDS epidemic for a specific demographic group and displayed it in their communities.

“The problem tree allows you to see things really the way they should be seen. It helps you see that there is more than one cause to the HIV problem,” Dr. Obidoa said.

Only after seeing the HIV/AIDS epidemic as it really is can effective solutions be explored and engaged, she said.

“For us in the Deep South, I think we just need to recognize that this is a problem,” she said. “We need to recognize that it’s not just a problem in Africa but a big problem here in Georgia as well. This disease is a disease of our social world, the way our world is designed.

“I’m particularly interested in bringing attention to the injustices of the epidemic — the role of social injustice in continuing to shape vulnerability to the infection and the systems that perpetuate these injustices.”

Dr. Obidoa presented findings from her work at the Population Health Equity Forum at Harvard University, where she was also selected as a Population Health Equity Fellow in 2016. She continues to research, educate community members and teach several classes on HIV/AIDS at Mercer.

Screening and prevention

Among the vulnerable are those who are homeless. Dr. Reddick, professor and chair of community medicine, has been working on HIV/AIDS testing and prevention among the homeless population in Savannah.

In 2016, he received a multi-year $1 million FOCUS (Frontlines of Communities in the United States) grant to provide HIV and hepatitis C screenings in nontraditional settings.

“Usually, when you’re a doctor and you think about screening for HIV, you think about a patient that comes to your office and you order an HIV test,” Dr. Reddick said. “What we were trying to do was get large-scale screening done because in Georgia we have the highest incidence of HIV of all the 50 states.

“We’re trying to get large scales of people tested for HIV and hepatitis C, so if they test positive, we can get them quickly linked to care and also get them on treatment as quickly as possible so that their viral load is down, and they’re not as likely to spread it to other people.”

This grant resulted in screening about 30,000 people each year.

As part of that work with Memorial Health University Medical Center and J.C. Lewis Primary Health Care Center, he discovered a lot of HIV preventative services, such as PrEP, weren’t available in the area. So, he began training local health care providers on how to provide PrEP to patients as well.

Dr. Reddick also started a needle exchange program after discovering that not many health care providers were offering the service. Needle exchange programs provide drug users with clean needles and syringes to prevent the spread of diseases, including HIV, through dirty needles.

“There’s a misconception that if you give people clean needles, you’re encouraging drug use and encouraging that behavior,” Dr. Reddick said. “But it turns out that — in all the studies of syringe service programs and needle exchange programs — you actually have lower recidivism rates.

“You have higher rates of people actually seeking drug rehab, and you also have a significant decrease in HIV and hepatitis C transmission.”

Some studies of HIV transmission among people who inject drugs show that needle exchange programs decrease HIV transmission up to 80%, he said.

“We’ve got some additional grant funding recently to supply a homeless community in Savannah — a specific community where there’s really high rates of IV drug use — with clean needles,” he said. “I’m hoping to have that rolled out by the end of this calendar year.”

In addition, the grant is funding a supply of naloxone, known by the brand name Narcan, which treats narcotic overdose.

“You see it’s kind of like a spiral that happens. HIV screening becomes HIV prevention becomes needle exchange program,” he said. “All of these things are connected.”

Marking the anniversary

Dr. Obidoa is the curator and chair of the Mercer Students Mark HIV @ 40 committee, which is focused on planning events to the mark the 40th anniversary of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

“My hope is that through these events our Mercer community will have the opportunity to reflect on the ways HIV/AIDS has impacted us and the world, as well as assist us in resolving to continue to fight against the disease,” she said.