On a breezy Saturday morning, Mercer University students carrying shovels and plastic grocery bags holding longleaf pine seedlings spread out across a burned landscape about 30 minutes from the Macon campus.

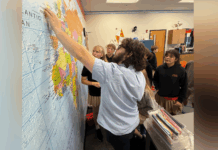

Working in pairs, the 11 students and three biology professors dug into the soil and planted the seedlings in shallow holes about 6 inches deep, patting down the dirt just below the bud. In less than an hour, the group had planted about 350 trees.

“This is some of the easiest tree planting,” said Dr. Heather Bowman Cutway, professor of biology, as she encouraged the students to take a selfie and drop a GPS pin on a tree’s location, so they could come back and visit it as it grew.

The tree planting was part of a long-term project to restore about 160 acres of land in Crawford County to its original habitat. More than 83,000 longleaf pines have been planted, thanks to a commitment from alumnus-owned Longleaf Distilling Co. to plant a tree for every bottle sold and nonprofit The Longleaf Alliance.

The goal is to “bring back a full, working ecosystem rather than a piece of land with trees, which is what it was pretty much before,” Dr. Bowman Cutway said.

Mercer bought the property in 2018 for the physics department to use as an observatory for its astronomy classes. The land includes a high hill, perfect for setting up telescopes and observing the stars away from the light pollution of the city.

At the same time, the biology department began using the property as a field station, studying the flora and fauna that live there. Human intervention in prior years, though, had altered the environment, Dr. Bowman Cutway said.

Loblolly pines, which are commonly used on commercial timber sites, were abundant. But they did not provide the ecological benefits of longleaf pines, which are naturally suited for the area, she said.

The property lies in the sandhill region, which is characterized by rolling hills and sandy soil. The area is susceptible to periodic fires, and longleaf pines are uniquely adapted to survive these harsh conditions, Dr. Bowman Cutway said. In addition, the trees promote the growth of plants that provide food for endangered gopher tortoises, whose burrows are used by hundreds of species for protection during fires.

The biology department worked with a conservation forester to come up with a restoration plan. This included logging the loblolly pines, applying herbicide to remove invasive plant species and holding a prescribed fire, Dr. Bowman Cutway said.

“What that did was give us a clean slate to plant longleaf pines,” she said.

Once planted, the longleaf pine seedlings look like long tufts of grass emerging from the ground. They’ll stay in this grass stage for several years, as its root system reaches out beneath the surface. These deep roots help the tree collect rainwater from the sandy soil.

During a fire, the long needles can burn, protecting the bud within. After the tree base reaches 1-inch diameter, it will grow 5 feet in one year, placing the buds safely above any future fire.

The trees will continue growing and maturing, nurturing the ecosystem below them for hundreds of years.

A professional crew planted the majority of trees, with the Mercer team planting the area closest to the observatory. A team from Longleaf Distilling Co. also planted about 350 trees on a separate visit. Prescribed fires will be used for maintenance, as is typical in thriving sandhill communities, Dr. Bowman Cutway said.

Care was taken so that trees, which will eventually reach a height of 70 feet, will not obstruct the view of the observatory.

Longleaf distillery’s commitment

Mercer alumnus Will Robinson and David Thompson opened Longleaf Distilling Co. in 2023 in downtown Macon. They had an idea: to restore the distilling tradition and bring back spirits that were once lost to time.

“One of the things that draws me to this industry and draws me to spirits is the rich history behind it,” said Robinson, who graduated with his bachelor’s degree from the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences in 2007. “These spirits didn’t pop out of nowhere. All of them have deep, deep traditions and histories behind them. And some of our spirits, especially things like our Italian amari, have been lost to history. It’s a category that was largely forgotten, and then its recipes were wholly forgotten.”

When looking for a name for the distillery, Robinson found parallels between the business’s mission and the longleaf pine.

“We were looking for something that was very Southern and was part of our shared history,” Robinson said. “You can kind of tell the story of Georgia and the story of the Southeast through the history of the longleaf pine and its degradation. …

“Now, we’re trying to rebuild what we broke in the past and trying to appreciate what we’ve lost by celebrating it and making sure that future generations have an opportunity to experience it.”

He wanted the distillery to give back, and planting a longleaf pine for every bottle sold seemed a natural fit. Dr. Bowman-Cutway heard about their plan and approached Robinson about partnering with Mercer to plant the trees at the field station. He said he liked the long-term trajectory of the project, the connection with Mercer and the idea of developing a teaching forest.

Students who work in the labs of Dr. Rebecca McKee, assistant professor of biology, and Dr. Barry Stephenson, associate professor of biology, already help conduct research on the property. Dr. McKee is studying the gopher tortoise, and Dr. Stephenson is researching amphibians and reptiles.

The sandhill community restoration could lead to additional research projects at the field station, Dr. Bowman Cutway said.

“It’s really bringing back a rare ecosystem,” she said.

Bottles supporting the mission are sold in Longleaf’s tasting room on Second Street in downtown Macon and its store online.