A Mercer University School of Medicine professor is part of a research team that has discovered two new species of ancient crocodiles in Africa.

Dr. Francis Kirera, associate professor of anatomy and former curator of hominid paleontology at the National Museums of Kenya, is a co-author of a study, titled “Giant Dwarf Crocodiles from the Miocene of Kenya and Crocodylid Faunal Dynamics in the Late Cenozoic of East Africa.” It was published in June in the journal Anatomical Record.

The discovery is a collaborative effort from several different research teams drawn from universities in Georgia, Illinois, Kansas, Minnesota, New Mexico, North Carolina, Tennessee and Madrid, Spain, as well as Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum in Frankfurt, Germany, and the National Museums of Kenya in Nairobi.

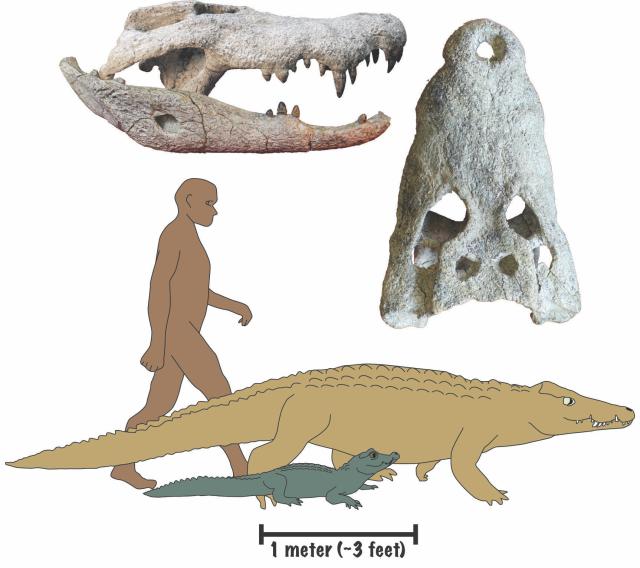

The researchers described two species of giant dwarf crocodiles, called Kinyang mabokoensis and Kinyang tchernovi, that existed 15-18 million years ago in the East African Rift Valley in parts of present-day Kenya.

Dr. Kirera was on the team that discovered a nearly complete skull of Kinyang tchernovi, which existed about 17 million years ago, at the Loperot fossil site in Kenya’s Rift Valley Province in summer 2016. Fossils of this species were also discovered at the Karungu site on the shores of Lake Victoria. Evidence of the other species, Kinyang mabokoensis, was found nearly a decade ago at Maboko Island in Lake Victoria, Western Kenya, Dr. Kirera said.

“We found this piece of bone embedded in calcium carbonate concretion, and we never thought it was important until it was cleaned. That’s when we found out it was an important discovery,” he said.

Dr. Kirera explained that most fossilized bones don’t come out clean, and they are turned over to experts who are trained in removing them from the solidified matter. It’s a process that can sometimes take a couple of years. After the skull was cleaned, it was analyzed and the new species confirmed.

This was Dr. Kirera’s first field research after joining the faculty at Mercer, and the team also included researchers from Midwestern University, Appalachian State University and the National Museums of Kenya, he said.

The giant dwarf crocodiles were as long as 12 feet and had deep snouts and large, cone-shaped teeth. They lived mainly in the forest and were a major predator of humans. By contrast, present-day dwarf crocodiles are about five feet in length and live primarily in the tropical forest wetlands of central and west Africa.

“The modern dwarf crocodiles tend to be more terrestrial. They spend time in water, but you’ll find them roaming in open environment, mostly in forest. We think the same thing was happening with these guys when they were present,” Dr. Kirera said.

“These crocodiles walked the earth 15 to 18 million years ago. During this period, the whole world was really warm. You go to places like Europe and North America, and it felt like the tropics. You see these giant reptiles all over. Their extinction is thought to have been brought by global cooling and subsequent disappearance of forest covers. We think probably that’s why they became extinct. The environment was changing.”

Dr. Kirera said the findings are especially significant because they show the ancestors of modern dwarf crocodiles were giants and they demonstrate how major extinctions can be linked to climate change processes.

Since 2018, Dr. Kirera has been conducting field work at 400,000- to 500,000-year-old sites located outside the East African Rift Valley in the Central Highlands of Kenya. He said his research team had a productive summer, finding new sites, fossils and archeological remains. Some of the new materials they are working on potentially represent new species that will be announced later. Dr. Kirera hopes to develop a program that will allow Mercer undergraduate students to work with him in Central Kenya.