A Mercer University research team has made a discovery that could lead to a treatment for illnesses caused by the Epstein-Barr virus, including mononucleosis and cancer.

Part of the herpes virus family, the Epstein-Barr virus is one of the most common human viruses, infecting most people at some point in their lives. It also is one of the herpes viruses known to cause cancer in humans.

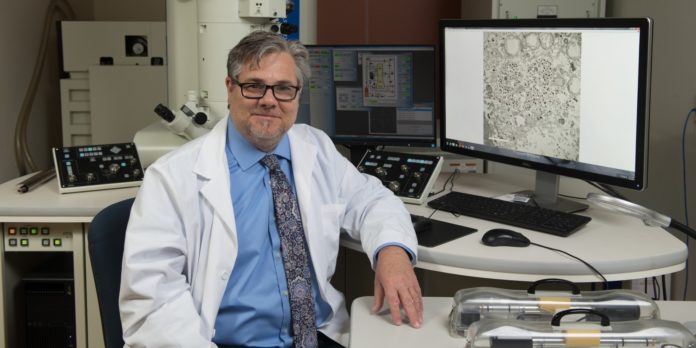

Dr. Robert Visalli, professor of biomedical sciences in the School of Medicine, and his lab have discovered an extremely small, key component of the Epstein-Barr virus, called the portal. The portal is critical in transporting the virus’s genetic material into a particle, allowing it to become infectious.

“We’ve been the first to identify and discover the portal protein of the Epstein-Barr virus, and we have potential antiviral compounds that affect the function of the portal,” Dr. Visalli said. “It’s interesting because if there is no portal, there is no infectious virus.”

The discovery was published in the March 2019 issue of the journal Virology.

The Mercer team’s goal is to discover a drug that affects the function of portals, so there could be a broad-spectrum treatment for use against not only Epstein-Barr but any of the herpes viruses, Dr. Visalli said.

“We’re working on a drug that you can give to a person, either in advance of being exposed to the virus or while they’re showing symptoms of the virus, to try to lesson the disease,” he said.

Electron microscope accelerates research at Mercer

A high-powered transmission electron microscope was instrumental in the discovery of the Epstein-Barr virus portal, Dr. Visalli said.

“Without the electron microscope, we would have no way of having isolated that portal component and looking at it,” he said.

The School of Medicine, with support from the Georgia Research Alliance (GRA), purchased the JEOL JEM-2100Plus Transmission Electron Microscope in 2017. GRA funded half of the $700,000 price tag, Dr. Visalli said.

The microscope is capable of collecting digital images at the cellular, sub-cellular and molecular levels, magnifying up to 1 million times and providing near-atomic detail. It uses a beam of electrons to create an image, as opposed to lower-powered microscopes that magnify using light.

This particular microscope, housed at the William and Iffath Hoskins Center for Biomedical Research on the School of Medicine’s Savannah campus, was only the second of its kind installed in the country, Dr. Visalli said.

“With GRA’s help, we were able to purchase the best microscope available that doesn’t cost millions of dollars,” Dr. Visalli said. “It’s a major advancement over the microscopes that we could have purchased ourselves.”

Prior to purchasing the electron microscope, researchers lacked the ability to perform in-house experiments and develop expertise with the technology.

“We had to ship samples or go to other universities to do the types of experiments we wanted to do,” Dr. Visalli said. “So getting the scope was great because now we could actually pursue some of the types of things we wanted to do in-house.”

The seven other universities in the GRA also have access to Mercer’s electron microscope, and Mercer has access to core facilities and equipment at those universities, as well, due to a memorandum of understanding signed in 2018.

Over the last year, about seven scientists from Mercer’s various campuses have used the microscope, including a scientist in collaboration with the University of Florida, said Dr. Maheshinie Rajapaksha, a research scientist who oversees use of the microscope.

“We can see the unseen now,” she said.

Highly sought-after technology

Mercer’s transmission electron microscope has another feature that’s been highly sought-after in recent years: the ability to do cryogenic electron microscopy.

Cryogenic electron microscopy allows scientists to freeze and examine their samples in the biological form.

“It preserves the sample in its physiological form so that your result is more accurate,” Dr. Rajapaksha said. “Now it’s becoming an increasingly popular method because researchers would like to not chemically preserve things.

“They like to actually see what is happening in the real environment.”

The surge in interest in cryogenic electron microscopy came after three scientists were awarded the 2017 Nobel Prize for developing the technology.

“The technology has exploded,” Dr. Visalli said.

‘There’s great utility for this’

The transmission electron microscope may be housed in Savannah, but it is available for any scientist at Mercer — or other universities — to use. It also has applications outside of the School of Medicine and could be used by researchers in other schools and departments, like engineering or chemistry, for example.

“There’s great utility for this technology in many different biological fields,” Dr. Visalli said.

Researchers interested in using the transmission electron microscope should email Dr. Visalli at visalli_rj@mercer.edu or Dr. Rajapaksha at rajapaksha_km@mercer.edu.