Alicia Hernandez didn’t plan on dropping out of high school.

Even after getting pregnant at age 14, she continued her schooling until a couple of incidents made her feel unsafe in class. That’s when she dropped out of 10th grade and started working.

Her mother stayed home with Hernandez’s daughter while the young mom helped support her family by working as a cashier at Bojangles’.

“But I actually loved learning,” Hernandez said, so she began studying for a GED certificate.

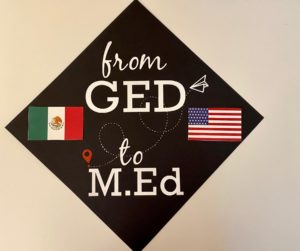

Less than three months later, Hernandez earned her GED diploma. But it would take over a decade to achieve the degree she has today: a Master of Education in Higher Education Leadership from Mercer University.

Against all odds

Born in Mexico, Hernandez moved to the U.S. when she was 3. Her dad worked on a farm, and her mom worked at a plant nursery.

As a young child learning to speak English, she often had to translate for her parents. Neither had graduated high school, having advanced only through the sixth or seventh grade, so she was often on her own when it came to schoolwork.

“Even in the lower grades, they weren’t really able to help me unless it was just like maybe addition or simple math problems,” she said. “But as far as writing goes or anything that had to do with English or history or anything like that, they weren’t really able to help.”

As a teen mom and first-generation college student from a family of Mexican immigrants, the odds of her furthering her education were stacked against her.

Consider:

- Only 40% of teen mothers graduate high school, and less than 2% finish college by age 30.

- Ten percent of Hispanic students drop out of high school, compared to 6% of their white counterparts, and lag other groups in obtaining a four-year degree.

- First-generation college students are less likely to enroll in college, and those who do are more likely to leave than their peers whose parents attended college.

But Hernandez had the tenacity to push on.

After earning her GED diploma, she wanted to go to college but didn’t know how to start.

“I didn’t know what to look for in a college. I didn’t know what questions to ask,” she said.

Hernandez enrolled at Lanier Technical College in north Georgia. She initially planned to get a two-year degree in accounting, but once she began attending classes, she realized how much she enjoyed learning.

“I enjoyed going to school. I enjoyed the homework. I enjoyed meeting new people, as well,” she said.

She wanted to continue at a four-year school but ran into roadblocks. Her credits from Lanier Tech wouldn’t easily transfer to most four-year colleges.

DeVry University would accept her credits, though, so even though she had reservations about the for-profit school, she transferred there.

“Then, I guess, life just happened,” Hernandez said.

She was exhausted from being a mom, working a full-time job and being the sole provider for her now four children.

“I decided to take a break. I was only planning on taking a semester off, and that semester turned into more,” she said. “This is why it took me like 10 years to complete it.

“That semester turned into a five-year gap.”

Eventually, she went back to DeVry. In 2019, she earned her Bachelor of Science in technical management with a concentration in accounting.

By then, she had been working in accounting for about 10 years and was employed as a staff accountant at the Georgia School Boards Association in Lawrenceville. Working there helped her realize her passion for education, so she started researching master’s degrees.

Life as Superwoman

That’s when she found Mercer.

She spoke with a counselor at Mercer about the Master of Education in Higher Education Leadership, “and he was phenomenal,” she said.

“He was telling me everything I needed to know, asking me questions about where I wanted to go career-wise, how I wanted to use this degree.”

With support from her job and her family, Hernandez enrolled in the program.

On school days, she’d leave her house in Gainesville at 7:15 a.m. and drive 40 minutes to her job in Lawrenceville. After work, she’d drive 20 minutes into Atlanta to attend class, then drive 50 minutes home, sometimes not getting back until after 11 p.m. Then, there was homework.

Hernandez said she often struggled with imposter syndrome, questioning whether she really belonged in college. But her children — Yessenia, 22; Giovany, 18; Jocelyn, 14; and Yazmine, 12 — were a great support to her, often sending her encouraging texts that helped her press on.

“My kids think I’m Superwoman, and I can do anything,” she said. “They were very encouraging, my biggest motivator, actually.”

Dr. Carol Isaac, associate professor in the Tift College of Education, said Hernandez was a hard-working student.

Hernandez’s capstone topic, “Nontraditional Students in Higher Education,” illustrated her life and concerns, Dr. Isaac said.

“It was well-written and inspiring considering all that she had going on,” she said.

As an accountant, Hernandez also helped with presentations in a finance course.

“She is a natural teacher, and her real-world experience made her instruction compelling,” Dr. Isaac said. “I cannot say how much I appreciated her contribution to that class.”

Hernandez graduated from the program in May.

Time to give back

Because of her experience, Hernandez encourages her children to make the most of their time in school.

“I just encourage them to go on trips if they can, so they can have a different experience than what I had,” she said. “I really just encourage them to go on out there and enjoy their high school and just their whole educational experience.”

With her new degree, Hernandez hopes to pay forward her newfound knowledge. She would like to start a nonprofit organization that helps at-risk students — she calls them “opportunity students” — stay in school and achieve higher education.

Hernandez also would like to create a scholarship for these students since, as an at-risk student herself, she struggled to find the money to pay for college, eventually taking out student loans.

She applied for a lot of scholarships but didn’t meet the qualifications for most. Many scholarships require applicants to be a graduating high school junior or senior, or they require a high-level of community involvement, which she couldn’t achieve as a single mom working full time.

Hernandez already has started an initiative called Stay In to Stand Out to encourage children to stay in school. She has spoken at a couple schools about her experiences.

“I talked about my background because I wanted them to be able to relate to me and see someone that was kind of in the same boat, maybe not exactly the same struggles they are going through, but just someone who was actually a high school dropout but decided to go back to school,” she said.

“I talked about my struggle to get into higher education, what I had to overcome, and how it would have been easier if I would have actually graduated from high school and stayed in school.”