Maison Clouatre has published four research papers, presented at conferences as far away as France, and is part of a team developing new traffic control algorithms for the Georgia Department of Transportation (GDOT) … and he’s only a junior at Mercer. An electrical engineering and math double-major, he joined the research lab of engineering professor Dr. Makhin Thitsa the first semester of his freshman year and has worked on a number of cutting-edge, advanced research projects since then.

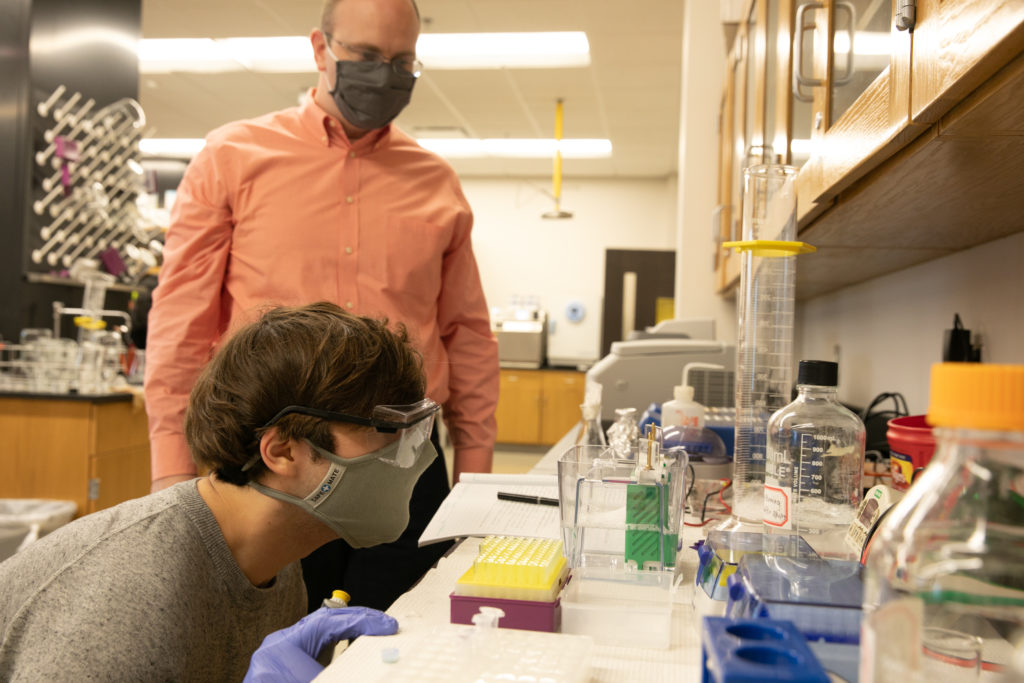

Opportunities like this are not uncommon for undergraduate students at Mercer University. They are encouraged to get involved in research early, and not just as observers.

“A lot of schools work with undergraduates, but I think what really separates us here is the undergraduates are participating and leading research that is producing novel discoveries. That’s in all disciplines,” said Dr. Kevin Bucholtz, professor of chemistry and director of undergraduate research at Mercer.

Almost all departments in Mercer’s undergraduate colleges have research courses in their catalog, and some academic tracks like the engineering honors program require students to complete research projects. Students are also welcome to get involved in research outside of their class requirements.

More and more Mercer students are taking advantage of the opportunities at their fingertips. From the 2009-2010 academic year to 2019-2020, the number of undergraduates enrolled in research-based courses increased 162%, according to a report from Dr. Bucholtz. In 2019, 32% of Mercer’s graduating seniors had participated in at least one designated research course.

In addition, the number of students who presented their research at regional and national conferences increased 242% over the past decade.

Setting the standard

Many Mercer researchers don’t have access to graduate students, so they rely on the participation of undergraduates to help advance their research goals, Dr. Bucholtz said.

Physics professor Dr. Frank McNally has two to four students do data analysis with him each semester for the international IceCube Collaboration. Mercer is one of 53 institutions in 12 countries that make up the collaboration, which is measuring data from a detector buried deep in the ice in Antarctica. Last year, Mercer was awarded a $15,000 grant from the National Science Foundation for the project.

“Research is a really collaborative exercise. It involves a lot of different skills,” he said. “Showing students what research really is and that they could do it in a meaningful way as undergraduates opens up a lot of potential doors for them.”

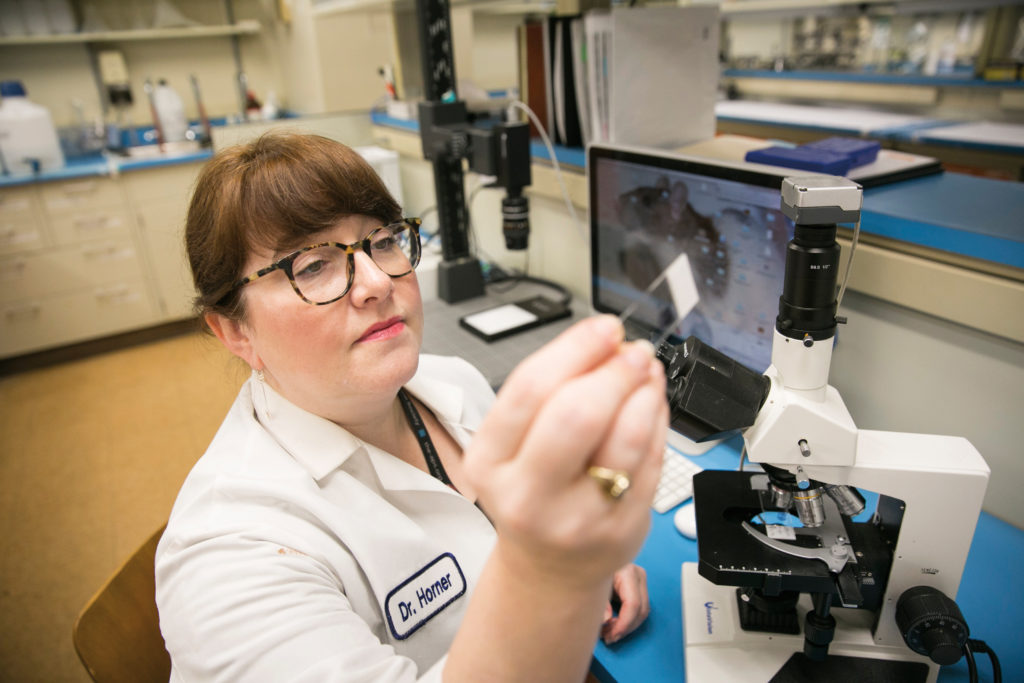

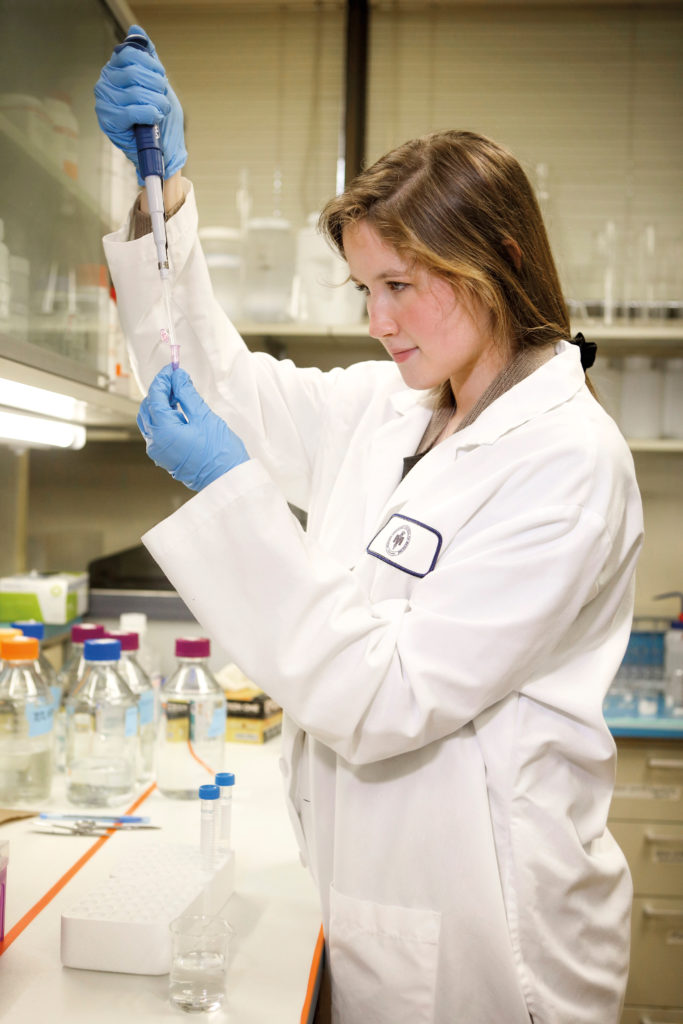

Each semester, at least one undergraduate student works in the lab of Dr. Kristen Ashley Horner, a pharmacology professor in the School of Medicine. She currently has eight students involved in a project to study neural pathways that contribute to meth addiction, which is funded by a $500,000 National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant.

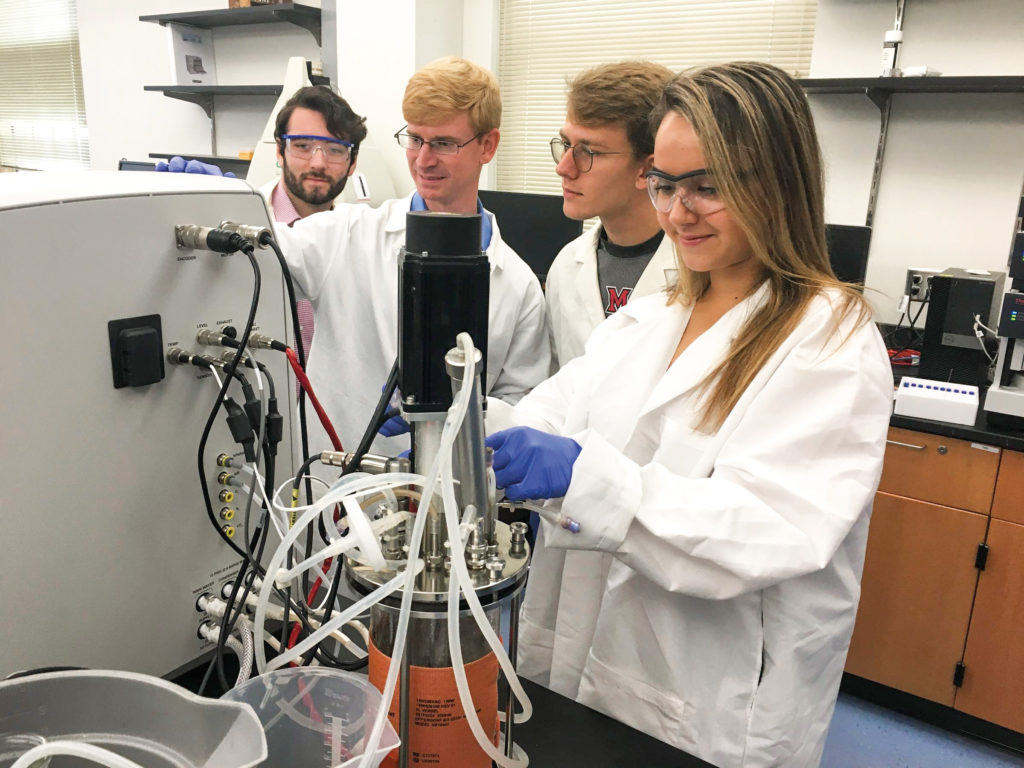

Similarly, Dr. Thitsa, an electrical and computer engineering professor, normally mentors one or two students at a time in her research lab, but she currently has nine students helping with a GDOT-funded project to effectively control traffic and coordinate traffic signals at the new diverging diamond interchanges.

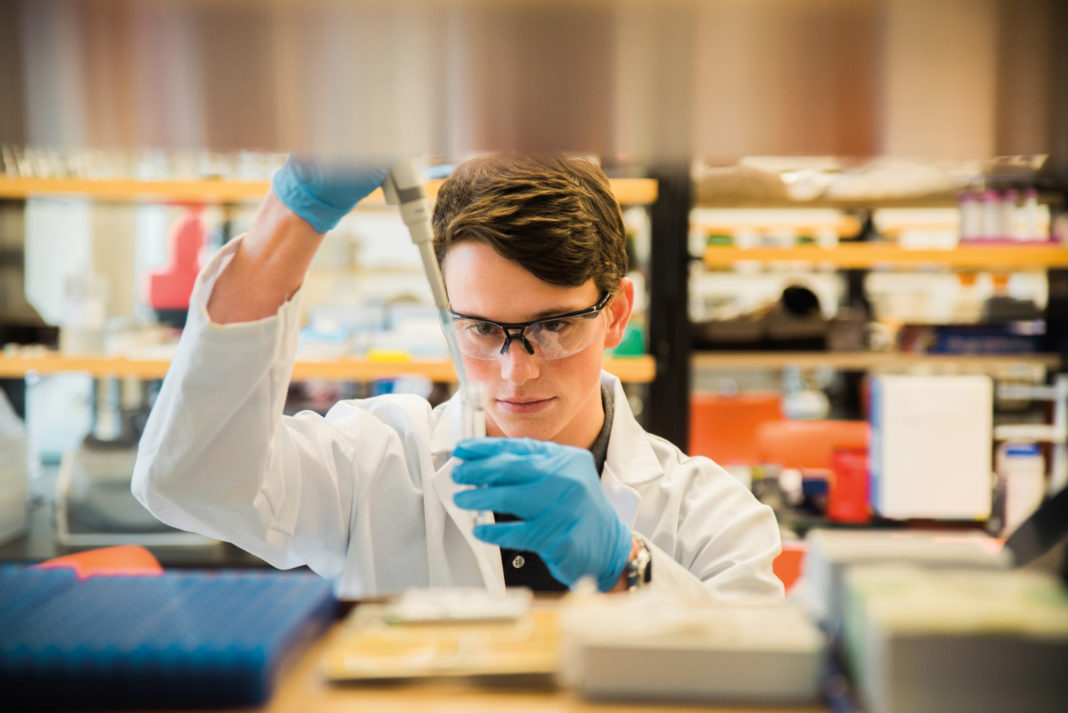

The projects they are working on are quite advanced, said Dr. Thitsa, who over the last five years has mentored three engineering students who have been awarded highly competitive Goldwater Scholarships, the nation’s most prestigious STEM scholarship for undergraduate students. She collaborates with faculty from Georgia Tech and MIT, and her students go head-to-head with the Ph.D. and postdoctoral students on those teams.

“There’s something really special going on at Mercer. We recruit our very bright, talented undergraduate students, and they get to take leading roles in these projects,” she said. “When I have them onboard to work on my projects, I don’t treat them as undergraduate students. I have very high expectations of them, and they know that. I push their limits, and they push their own limits. We are putting the standard of research very high for the undergraduate students.”

Students who can do this level of quality research have endless opportunities, whether they go on to Ph.D. programs or into the industry, she said.

“It really sets students up for future success,” Dr. Horner said. “For a student interested in pursuing a career in research, it’s crucial for them to have that experience as an undergrad. For students going into medicine, it’s important to see what happens before you go to the clinic and the patient.”

Fostering a love of science

Research opportunities ultimately led Clouatre, one of Dr. Thitsa’s Goldwater Scholars, to choose Mercer over other prestigious institutions to which he had been accepted. As a high school student, he was familiar with Dr. Thitsa’s work and contacted her, and she expressed a willingness to work with him if he came to the University.

“I knew that I wanted to be involved in this undergraduate research, and if I went to a larger school or one without Mercer’s reputation for including undergraduate students, I wouldn’t have had that opportunity,” he said. “Every single one of my peers who wants to be in a research lab is in one. While they must first express that interest to a faculty member, at Mercer there is always space for an interested student to be involved in the research of their choosing.”

Under the wing of Dr. Thitsa, Clouatre has tackled a number of unique research projects related to control theory, including work with high-power laser microscope systems, traffic control networks, quadrotor drones and autonomous cars. Clouatre said he wouldn’t be the researcher that he is without an adviser like Dr. Thitsa who welcomed and encouraged his ideas. His goal is to obtain a Ph.D. in engineering related to control theory.

“He is going to be somebody who is going to do great things,” Dr. Thitsa said. “He works extremely hard, and it’s such a joy to work with those students, because we feed off of each other’s energy. They say I motivate them and inspire them but, from my point of view, they inspire me.”

Mercer’s BOMM program for sophomores, which combines biology, organic chemistry and mathematical modeling, gave Luke Jones a reason to be passionate about science and led to an incredible mentorship. Dr. Linda Hensel, professor and chair of the biology department, invited him to join her lab after he finished the BOMM and then to participate in the Mercer Undergraduate Biomedical Scholar (MUBS) summer program.

Jones has remained a part of Dr. Hensel’s research team, doing work that focuses on antibiotic resistance. Now a senior, he’s currently training students who will continue that work after he graduates. His research experiences led him to want to pursue a career in medical research, and he is in the process of applying to combined M.D./Ph.D. programs.

“Mercer has allowed me to get involved early in a project that I could continue for several years,” he said. “Mercer is really great at enabling students to get involved in projects and stay involved in projects that are going to be career-developing opportunities that you might not get at other institutions.”

Kayla Kelley, a senior chemistry major who plans to go to medical school, participated in the MUBS program the summer after her freshman year and loved the research experience so much that she asked to work in Dr. Horner’s lab. For Dr. Horner’s NIH project, Kelley has been looking specifically into the role that arc protein in the brain plays on addiction.

“Having that exposure so early to clinical science, it really kind of fostered my love for science. What makes Mercer unique is there are specific opportunities where faculty want you to come and see what they do,” Kelley said. “The professors genuinely care about you and want you to know what’s going on and be open and honest about teaching.”

Discovering passions

These early research experiences sometimes change the trajectory of students’ careers and open their eyes to new opportunities. Alumni Dr. Leslie Aldrich and Dr. Andrew Jones entered Mercer wanting to be doctors but decided to go in different directions.

Dr. Aldrich, a 2008 graduate in chemistry, worked with Dr. Alan Smith in the biology department to develop a procedure for the detection of tick-born illnesses during her sophomore year and contributed to an organic synthesis project with Dr. Bucholtz her junior and senior years.

“I was originally on the pre-med track, and these research experiences changed my mind, in a good way,” she said. “They gave me the opportunity to think about what I am passionate about and what’s most important to me. What I realized by doing undergraduate research is that basic science and research can help improve human health, and that’s what I felt like was more of my calling.”

Dr. Aldrich went on to earn a Ph.D. at Vanderbilt University and complete a postdoctoral fellowship with Harvard University and the Broad Institute. She fell in love with organic chemistry as a student at Mercer, and now she teaches it at the University of Illinois at Chicago. She also runs a lab that studies a cellular process called autophagy.

“The faculty at Mercer create this delicate balance between this one-on-one mentorship and giving you challenging projects that allow you to work independently,” Dr. Aldrich said. “This really enabled me to learn how to deal with failure but also deal with complex problems that may not have an immediate answer. The way the professors would design projects and classes provided additional opportunities to hone your skills.”

Dr. Jones, who graduated in 2012 with a bachelor’s degree in engineering and a master’s degree in environmental engineering, found his interest piqued by biological research after assisting on a project his sophomore year with Dr. Michael Horst in the School of Medicine.

After a Mercer On Mission trip to Mozambique, he completed a water treatment analysis project with chemistry professor Dr. Adam Kiefer. He also worked on a solar distillation unit to purify saltwater and a project related to the removal of fluoride from groundwater with Dr. Laura Lackey, now dean of the School of Engineering. These experiences led him to want to pursue a Ph.D. in chemical and biological engineering, which he earned at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

“These research experiences are the reason I ended up where I am today,” said Dr. Jones, who is now an engineering professor at Miami University in Ohio and runs a metabolic engineering research lab. “I came into Mercer wanting to be a medical doctor. What I learned is that I have a passion for discovery. … I credit the one-on-one direct mentoring I received from several Mercer faculty members as a model for my current lab.”

As he strives to impact the world outside of academia with his research, translating novel discoveries into technologies that directly improve human health, Dr. Jones said Mercer’s “Research That Reaches Out” mantra resonates with him. The tagline, coined in 2014, perfectly captures what has come to be known as a hallmark of the Mercer experience — the ability for all students to participate in high-impact research focused on real-world problems.