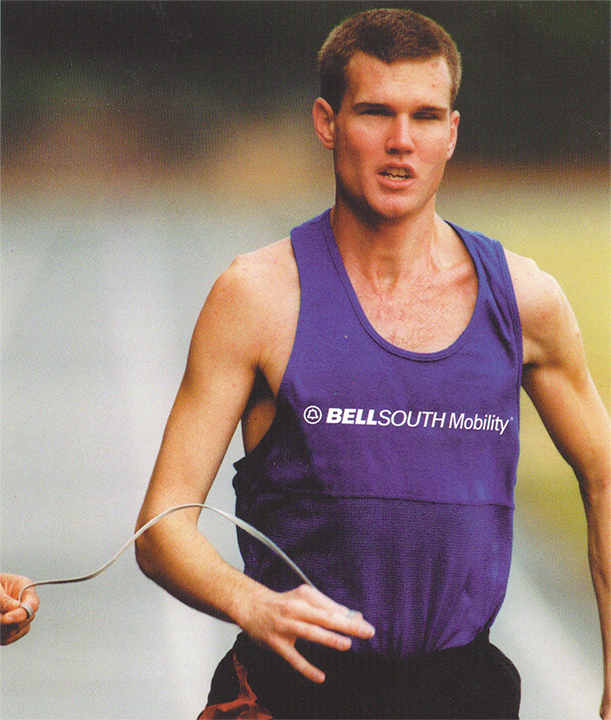

When Tim Willis first lined up for cross country practice at Shamrock High School, no one could have guessed that the teenager using a blue shoestring as his guide would one day become the fastest blind distance runner in the world. His coach had devised a simple but ingenious system — a blue shoestring connecting Willis’ hand with a teammate’s. That thin cord became his lifeline, his compass and, ultimately, his symbol of freedom.

Diagnosed with an eye condition called Coats disease as a child, Willis lost his vision completely by age 10. But blindness, he decided early on, would not dictate his limits. He wrestled in high school. He ran in college. And he did both with a fierce sense of independence. At Georgia Southern University, he made history as the first blind cross-country runner to compete in NCAA Division I competition — a trailblazer tethered not to limits but to possibility.

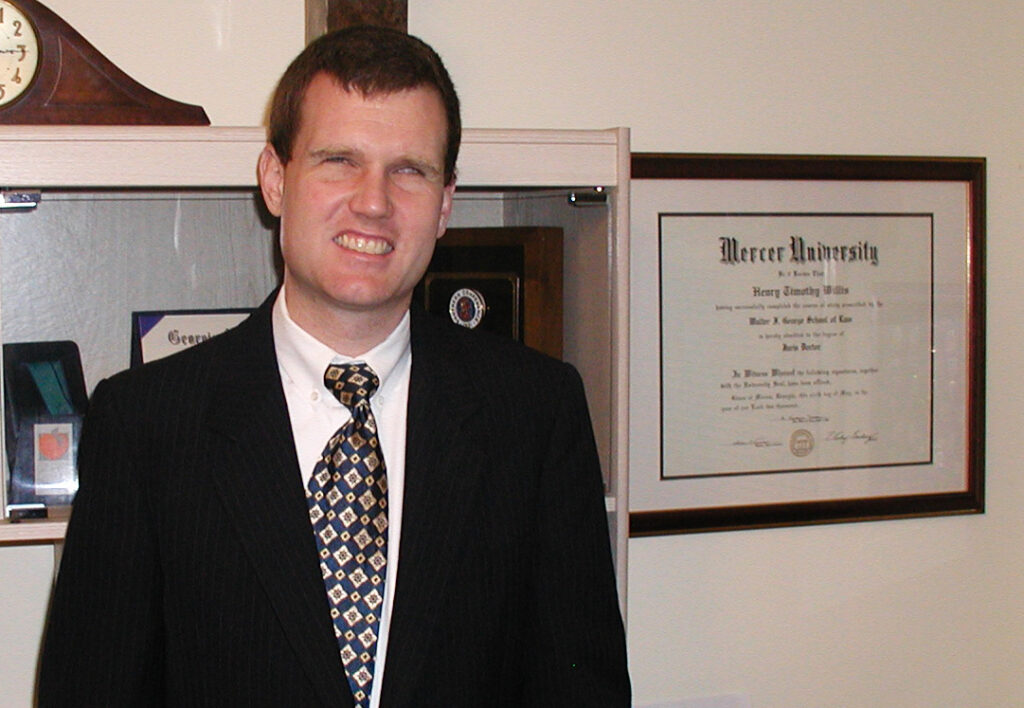

“When I got involved in cross country and track and field, I kept improving,” said Willis, who graduated from Mercer University’s School of Law in 2000. “That gave me the motivation and drive to continue.”

From 1990 to 2000, Willis’ journey carried him from local trails in Georgia to stadiums around the world. In Berlin in 1994, he captured gold in the 10,000-meter race at the World Championships. By the time he retired, he had set two world records and 12 national records, 10 of which still stand. At the 1996 Atlanta Paralympic Games, he earned four medals — silver in the 10,000-meter race and bronze in the 1,500-meter race, 5,000-meter race and 1,600-meter relay. Four years later, at the Sydney Paralympic Games, he added another bronze medal to his collection.

“Looking back on my running career, it’s hard to isolate one single best memory moment,” he said. “But having the 1996 Paralympic Games in my hometown of Atlanta was definitely special. That experience, the consistency of training and the friendships I made all stand out.”

That same year, his athletic success unexpectedly opened another door.

“My sponsor at the 1996 Paralympic Games, BellSouth Mobility, offered to pay for law school as a bonus for my 1996 medals,” he said. “That support made Mercer Law possible for me.”

By then, Willis had become a familiar name in Georgia sports and advocacy circles. He earned the status of Eagle Scout as a teenager, was honored as Georgia’s Blind Person of the Year at age 24, and by 26, he’d run alongside President Bill Clinton. He received the Cabrini Medal of Honor in 1996 for his inspiration and advocacy.

At Georgia Southern, he had earned the President’s Award and was named Outstanding Political Science Student before graduating in 1994. His alma mater later inducted him into its Athletics Hall of Fame. Today, he awaits yet another honor: induction into the Georgia Sports Hall of Fame at the 70th annual ceremony on Feb. 21.

But even as his accolades piled up, Willis never saw running as his only finish line.

“I’d always dreamed of becoming an attorney,” he said. “Law, like running, takes focus, rhythm and endurance.”

While training for the 2000 Paralympics, he enrolled at Mercer Law School.

“When I visited Mercer in 1997, I could tell it was the right fit,” he said. “The people were welcoming, and I could live right across from the law school, which made life a lot easier. Assistant Dean of Student Affairs Mary Donovan and others gave me confidence that I could succeed.”

Mercer equipped him with the tools to thrive.

“In the late 1990s, electronic books weren’t common,” he said. “So I had to get my materials early, scan them into my computer, and take exams using a screen reader. Mercer’s faculty and staff made that possible.”

He graduated in 2000 with the Dean’s Distinguished Service Award, one of the school’s highest honors for leadership and service. When he returned from Sydney — bronze medal in hand — he learned he had passed the Georgia Bar Exam.

Willis’ legal career began quietly but grew quickly.

“Although it wasn’t my original goal to be a solo practitioner, it just happened,” he said. “People from my network started bringing me small matters, and that led to work in disability rights.”

That early work became his calling.

“I was approached to work on several policy and litigation matters for the disabled community,” he said. “I realized how hard it was for people with disabilities to find adequate legal representation, and I wanted to fill that gap.”

He soon joined the Disability Law and Policy Center of Georgia, tackling landmark cases that improved accessibility and independence.

“We worked on major issues like MARTA’s transportation services for passengers with disabilities,” Willis said. “That litigation led to real structural changes in how public transit served people in Atlanta.”

In 2008, he took his advocacy to the national stage, joining the U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Committee in Colorado Springs, Colorado. There, he ensured federal funds supported programs for athletes with disabilities and served as an ombudsman for Team USA during the 2008 Beijing Paralympic Games.

“I’m proud of the impact we made,” he said. “We helped create programs that expanded Paralympic opportunities for veterans and communities across the country.”

Today, Willis lives in Chattanooga, Tennessee, where he balances his law practice, consulting work and advocacy.

“I still maintain my Georgia law license,” he said. “My work now includes personal injury, wills and estates, nonprofit governance, and disability rights. I also consult with nonprofits on sustainable programming and fundraising.”

Though he stopped competing after Sydney, running still pulses through his life.

“I ran recreationally six or seven days a week until my knee replacement in 2017,” he said. “Now I get joy from following younger runners, especially the kids of old teammates and friends.”

At 54, Willis sees his career — and his life — through a broader lens.

“As an athlete, progress was easy to measure — times, distances, medals,” he said. “In law and advocacy, change takes longer. I’ve learned that real impact happens over years, sometimes decades.”

He continues to pour his energy into causes that expand access and opportunity, especially for people with disabilities.

“A big focus for me lately has been on protecting voting access,” he said. “I want to make sure every voice, including mine, can be heard.”

Looking ahead to his Georgia Sports Hall of Fame induction in 2026 and the Los Angeles Paralympic Games in 2028, Willis remains grounded in gratitude.

“Running taught me how to keep moving forward, no matter the obstacles,” he said. “That’s what life — and law — are really about.”

His 1996 Paralympic medals and racing spikes now rest in the Georgia Sports Hall of Fame, glinting reminders of a man who turned a blue shoestring into a lifelong symbol of courage, conviction and faith.